Part II: More information about the Cherokee Nation Official Tear Dress

Information compiled & written by Wendell Cochran, Cherokee Master Craftsman and National Living Treasure in the Field of Traditional Clothing.

An Interview with Marion Hagerstrand, daughter of Jack Brown, former Superintendent of Sequoyah Indian School during the 1940’s and for whom the Jack Brown Youth Shelter is named.

This is the account of the Cherokee Tear Dress according to the recollections of Marion Hagerstrand, the wife of Col. Martin Hagerstrand who was the founder and Executive Director of the Cherokee National Historical Society at TSA-LA-GI. Mrs. Hagerstrand is an enrolled member of the Cherokee Nation and lives in Tahlequah, OK. Although Marion was not involved in the day-to-day operations of the facility, she was a constant companion to the Colonel and was privy to all of the planning and development of the grounds, the buildings and the outdoor Theater from it’s earliest conception through development and construction. She is a knowledgeable source of tribal history in the formative years of the modern Cherokee Government during the 1960’s and 1970’s.

Mrs. Hagerstrand was actively involved in the Outdoor Drama, The Trail of Tears. The drama opened in 1969 as a brand new production with a script by Kermit Hunter. Marion, who is an accomplished seamstress, volunteered to work in the costume shop as a stitcher during the rehearsal and construction period leading up to the opening.

Because the Trail Of Tears drama is a semi-fictional historical accounting of the Cherokee at the end of the trail in 1839 through the trouble and turmoil as they established a government and settled into their new homeland in the west, costumes for the drama had to created from scratch. The costumier for the first year was a New York trained designer who knew little about Indian or what they wore historically. Her costumes for the white people were copies of the 1830 to 1860. Dresses for the women were a problem because there were not any documents or photographs she could copy. It was decided that she would dress all of the Cherokee woman characters in replicas of the Tear Dress that had been made for Virginia Stroud. It was the only existing example of what “might” have been worn. Of course, the original tear dress had only been authenticated back one hundred years, which would have been after the civil war. The trail had taken place 30 years earlier.

Anyone who has studied fashion history by looking at paintings and magazine illustration of the period knows that clothing fashions changed dramatically through out the early half of the 19th century. Especially, women’s clothing. Skirts got wider and heavier, sleeve got bigger and longer, fabric became brighter and waistlines went up and down like a thermometer. Hoop skirts were introduced, thanks to the industrial revolution that could produce lightweight spring steel. The tear dress reflected the style of the latter part of the century. But, since it was the only garment that could documented as having belonged to a Cherokee woman, it became the only style and design choice that the costumier, Mrs. Hagerstrand and the Executive Director of the Historical Society, Col. Hagerstrand, could agree upon.

Mrs. Hagerstrand credits the costumier for making the first pattern for the tear dress. On the day the people in the costume shop began work on building the costumes for the show, there was only two existing dresses: the original trunk dress and the one currently worn by Virginia Stroud. No one had thought about drafting or cutting a pattern of the dress to make more for future Miss Cherokee to wear.

The prototype dress from the trunk was owned by Wynona Day, a Cherokee lady and a member of the search committee appointed by Chief Keeler. I need to correct a misunderstanding of a fact, I have for years understood that the dress was miraculously “discovered” in a trunk that once belonged to some anonymous person in North Carolina. I have recently been told that the dress actually belonged to Wynona Day’s Grandmother or great-grandmother and that it had in truth been stored in a trunk. She had come across it by chance after she inherited her mother’s belongings. She remembered having seen the dress and had retrieved it for the committee to examine. As far as everyone I have talked to know, that dress is still in the possession of the Day family. Wynona is now deceased. Her only heir is a son and his whereabouts is unknown.

To return to the saga of the dress in association with the drama, Mrs. Hagerstrand recounts that they called upon Mrs. Day for use of the dress so they could copy it. She gladly brought it and allowed the costumier to examine it thoroughly. The costumier measured each section of the dress, recorded the dimensions, and noted the grain direction of each piece. Mrs. Day jealousy guarded the dress and never let it out of her sight. She absolutely would not leave it or let them keep it overnight. After the dress was measured and many notes about the way it was constructed were recorded, Mrs. Day took her dress and left. That was the last recorded study of the dress. Evidently, it was also the only time anyone attempted to make an original pattern.

The term pattern is a misnomer. It was actually a cutting guide drawn on a grid of lengths and widths according to the grain of the fabric. Because the dress is simply constructed entirely of squares and rectangles, a paper pattern, as anyone who makes tear dresses has subsequently discovered, a paper pattern is practically useless if not a hindrance. It is cumbersome and unwieldy to try to layout and pin large pieces of paper to fabric that will get torn anyway. The best method then as now is to mark the lengths of each piece along the salvages, clip it and rip it. Which is what the costume shop did when they made the first batch of tear dresses for the drama.

Even with her meticulous notes and mathematical measurements, Mrs. Hagerstrand remembers that making the first several dresses was an experience that tried the costumier’s soul. She had to devise a system for putting the dress together so she could supervise the stitchers. The trickiest parts of construction were in figuring out how to inset the sleeve gussets — and then setting the lower part of the bodice onto the yoke.

At the end of the season, the costumier took her notes for cutting the dress and returned to New York The following year, I was hired as the Costumier Designer. I owned my own set of period costume patterns for men’s suits and American women’s dresses and had taken a college course in how to draft patterns. I had never seen or heard of a Tear Dress. Marion taught me the rudiments of making a tear dress the way she had been instructed by the first costumier. She also showed me some of the Tear Dresses that had been made the previous season. They were not pretty.

The costumier had cut and made the theater dresses in ways that suited their use as costumes. She had taken shortcuts to get them made in the shortest time allowed by a crew of people who were not necessarily accomplished seamstresses. To be blunt, the Tear Dresses were awful; they were ill fitting, poorly made and shapeless. She had put zippers in the front so the actresses could get in and out of them during quick changes. To save time, the neck was finished with commercial bias tape, which had let the necklines stretch. She also had gang-cut all the dresses so that, except for a few extremely large one, they were all exactly the same size – big and loose. During the fittings before the first dress parade, it was impossible to tell how the dress was supposed to fit. They were the ugliest things I had ever seen. By comparison, prison dresses would have been a high fashion statement.

My job as costumier was to make new costumes and the director directed me to make more Tear Dress for the cast. He wanted to use them in a dance number. So, I made Tear Dresses. It was a chore to use the examples I had at hand to try to figure out how to make Tear Dresses that looked good, fit well and still keep the construction historically correct using only squares and rectangles. By trial and error, I discovered the tricks of constructing the Cherokee Tear Dress. I also picked a lot of seams out after the rest of the crew had gone home for the night in the process. I finally realized that the looks of the dress depended entirely on proportions of length and fullness to the body of the person wearing it.

I also discovered that the Tear Dress is not difficult to make if you follow a system of sequential steps in putting it together. I also found out that it takes more time to make a simple tear dress than anyone can imagine. There are no short cuts. The trick is in setting the gussets into the bodice and sleeves before those pieces get pinned and sewn on the outside onto the yoke.

That summer of 1970, Marian Hagerstrand, a high school girl named Cathy Cunningham, a Creek woman whose name I can’t remember and who was also in the show, and I made a lot of new Tear Dresses. We gathered yards of ruffles, sewed miles of seams and make innumerable buttonholes. By the time the drama opened, we had become the first and only professional Tear Dress experts in the Cherokee Nation and the world. Every other Cherokee Tear Dressmaker since that time owes their knowledge of the craft in no small part due to the efforts and labor of the four of us during those weeks in the costume shop at Tsa-La-Gi.

Marion Hagerstrand continue working each summer at the Drama for many years until her husband was forced out of position. Miss Cunningham finished her education, got married and never continued her interest in theater; the Creek lady went into Indian education and sewed only as a hobby for herself and her family. I continued as a costumier and branched out into making custom made garments, Indian crafts and worked as a historical researcher for the Cherokee Nation and Bilingual Education program, among several other jobs of no consequence. In 1989, the Tribe and the Cherokee National Historical Society awarded me the title of Master Craftsman and National Living Treasurer in the Area of Traditional Cherokee Clothing.

This is the account by Virginia Stroud of the very first Cherokee Tear Dress ever made any modern day Cherokee woman.

Virginia attended Bacone College when she first heard about the Miss Cherokee contest. She was not raised with close ties to the Cherokee people and knew very little about her own heritage, her parents’ people or her traditional background. Her mother, who was from Marble City, had made a conscience decision to not tell her girls about their ethnic background because she did not want to subject her two daughters to the pain she had experienced during her childhood while attending U.S. Government run boarding schools. Virginia’s father and mother took their young children to California as part of the B.I.A.’s relocation program that was instituted after the Second World War. After living in Californian where the family lived in racially mixed neighborhoods. The two girls returned, while still young, to Oklahoma, for family reasons, Virginia was placed in the Murrell Children’s Home on the campus of Bacone College at Muskogee, Oklahoma. After completing high school, she enrolled in college where she immersed herself in the Indian art program. Most of her college expenses were provide by various means of grants and scholarships. At the beginning of the school year when she was 19, she needed fifty dollars to finish paying her tuition and class fees. She had never seen or met a Miss Cherokee and the only meaningful thing she knew about the contest was that the winner got a cash prize. That was the only reason she entered the contest during the National Holiday celebration.

To her surprise she won and got the money. After Cherokee Holiday, she had few other duties associated with her title except for attending rare public events with Chief W.W. Keeler, so she returned to Bacone to finish out the school year. That fall, the tribe automatically entered her in the Miss Indian Oklahoma pageant sponsored by the Indian Women’s Federated Clubs and she won the state title. She entered the state contest wearing a traditional leather Kiowa dress complete with Plains Indian style bead work, moccasins and feather fan. Virginia borrowed the outfit from the Ahtone family who had adopted her in the Kiowa Indian way; Sharon Ahtone was her closest friend and school chum.

The following her first year in college, Virginia accepted a job as an art instructor at an children’s summer camp to earn money to pay her college expenses. As the reigning Miss Indian Oklahoma, however, she was expected to represent Oklahoma in the Miss Indian America contest. Her plans were to enter the contest and as soon as it was over, report to the camp and teach. To her surprise, the judges selected her as the new Miss Indian America. From that point on, her plans changed drastically and she never did report to the summer camp.

Ms. Stroud flew back to Tulsa and was met by a personal representative of Chief Keeler. It was at that point that Chief Keeler and his handpicked committee of Cherokee women began their search to find a suitable Cherokee outfit for her to wear. Two of the women on the committee were Marie Waddle, a BIA employee, and Wynona Day, the daughter of an influential Cherokee family from the days before statehood. Wynona Day is the person responsible for discovering the dress that became the prototype and model for the modern day Tear Dress.

As soon as the committee of women decided that Wynona’s Grandmother’s hand made dress would be perfectly acceptable for the new Miss Indian America to wear as a representative of the Cherokee people, Chief Keeler concurred. The next step was to get a new Tear Dress made for Virginia to wear.

Virginia Stroud’s sister, Elizabeth Walters, who she calls B, made the new dress. She copied the dress line for line, including duplicating the reverse applique on the decorative bands over the shoulders and around the skirt. The dress has a square neckline and no buttons or buttonholes. It closes with hooks and eyes; however the original had no visible means of fastening the dress with modern closures. We believe that according to fashion research, it was common practice for women to use broach pins to fasten blouses and those garments known as waists. Today we would probably just use safety pins.

**Accessories created and added to the outfit to enhance the look of tradition.

While the new dress was being made, the committee commissioned Willard Stone, a renowned Cherokee artist, and woodcarver from Locust Grove, Oklahoma to design and make some kind of regal crown for her to wear. He designed a crown of copper, to reflect the only kind of metal that was available to the ancient Cherokees, which he engraved with a fan of wild turkey tail feathers surrounding the Great Seal of the Cherokee Nation floating over a narrow horizontal field imprinted with wild turkey tracks to signify the woman’s importance in nurturing and teaching the next generation. Miss Stroud’s crown was engraved with her title of “Miss Indian America”. Stone made a second crown with exactly the same design symbols except that the title read “Miss Cherokee”. Ms. Stroud now has personal possession of Miss Indian America’s crown. Stone’s crown

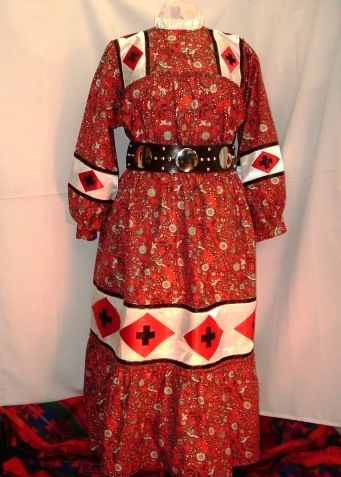

Wendell Cochran & Model wearing Traditional Tear Dress, with calf-length White Turkey Feather Cape. Photo by Charlie Soap, Wilma Mankiller’s husband.

for Miss Cherokee is archived at the Cherokee Heritage Society Museum. A facsimile of the Willard Stone crown for Miss Cherokee was commissioned and purchased from Bill Glass, Sr., a Cherokee silversmith from Rose, Oklahoma. For several years, a new Miss Cherokee crown was made each year and the girls were allowed to keep their crowns. That practice has been discontinued; the crown is passed along to the next new Miss Cherokee.

To complete the symbols of Cherokee royalty, the women made two calf-length white turkey feather capes: one for Virginia Stroud and another for next Miss Cherokee who was to be selected at the Cherokee Holiday. Each cape was covered from neck to hem with overlapping rows of three-to-four inch long turkey feathers. Virginia’s completed ensemble was magnificent and unique. No other tribe had any thing similar. In spite of the fact that her entire outfit, dress, cape and crown were completely new and recently invented as an old tradition created, they always seems perfectly right as an acceptable form of traditional dress.

Over a period of about ten years, subsequent Miss Cherokees were required to wear the official copy of both the feather cape and crown in their public duties throughout their reigning year. The feather cape was both hot and heavy. It eventually became too ratty to wear and was retired to the Cherokee National Museum. The shape and symbolism incorporated in the copper crown has been copied and reinterpreted by several other Indian tribal groups for their Indian Princesses.

**Some specific notes about what makes a Tear Dress more authentic than one that is simply traditional.

I received a telephone call, coincidentally, this morning before I came to the office to finish this report (April 5, 2000) from the daughter of a friend of mine who wanted information about the Tear Dress.“Which,” she asked, “is rally authentic for the trim on a Tear Dress? Three rows of ribbon or the cut out stripes?” Someone who said she knew how to make tear dresses had told her that ribbons were actually the kind of trim to use.

“No” I told her. “Ribbons are a lazy woman’s way of making more money by doing less work.”

The difference is like the difference between a Corvette and the official lead car at the Indy 500. They both started with the same basic design and assembly method, but the Lead Car is supped-up and has a lot of racing stripes and decals plus better upholstery and gadgets inside.

A tear dress with ribbons is a tear dress; a tear dress with reverse or pierced appliques is an Authentic Tear Dress. Virginian Stroud’s Tear Dress has reverse applique large and small squares (navy blue) applied over a bright complimentary colored piece of cloth (medium gold-yellow), which is then slip stitched onto the dress (a deep red-orange print). The colors of the reverse applique and contrast fabric pick up the colors of the small print figures in the dress fabric design.

Cherokee girls who go to a lot of pow-wows like ribbons because the colors are brighter and shinier than ordinary fabric. They also seem to like multiple bands of ribbon in various shades of “Indian” colors. Bands of ribbon trim are also of varying widths. From a distance, as seen across the dance circle, ribbon trimmed dresses do make a good show. They are just as colorful and dramatic as any of the elaborately trimmed and adorned Plains Indian Tribe’s dress.

**Sleeve and Skirt Lengths.

The trunk dress and its copy made for Virginia Stroud were less full and shorter than tear dresses now being made. By comparison, tear dresses made in the late 1970’s and early 80’s look skimpy next to a recently made dress. The skirt of Virginia’s dress is three-quarters length, the same length as a perhaps a buckskin dress that is worn over leggings. From the front, the hem ends a little lower than mid shin. This is a graceful look for young thin women because the hem hangs horizontal to the ground. On women with large hips or big butts, a three-quarter dress is not pretty sight, because there is no way a straight gathered skirt is going to hang straight. The hem naturally hikes up in back and if they bend over, it exposes the back of the knee and too frequently more than man or beast can stand. There are dressmaker’s tricks that can be used to compensate for the extra length needed in the back panel, but the top of the back skirt panel must be cut. It cannot be torn.

Prior to the reign of Miss Cherokee Mary Kay Henshaw, now Henderson, no Miss Cherokee wore a floor length Tear Dress. They were either three-quarter or slightly above the ankle length. Whether by design or badly measured, Mary Kay’s dress was full length and the back of the skirt swept the ground by a couple of inches. I personally liked the look and it made her appear absolutely regal — despite her height and size. She was tall for a Cherokee woman and probably wore a size 22 or 24 dress. When she made a public appearance she didn’t just enter a room, she conquered it. Since then, it has become common for Cherokee Pow-Wow Dancers and Princesses to wear full-length skirts. When they round dance or compete in the traditional cloth category, the back of their skirts sweep and fold gracefully with each dip and turn.

**Sleeve Length.

The sleeves on the Stroud dress are three-quarter length finished by a wide band that is decorated with reverse applique. The width of the band approximates the same width as those across the shoulders. There is no ruffle on the bottom of the band. All of the first tear dresses I made had three quarter length sleeves. I do not remember when I started making the sleeve wrist length, but I believe that I made them longer in response to my customer’s complaints that three-quarter sleeves were not comfortable to wear. They would not stay pushed up where they were suppose to be. When they fell, the sleeves lost its puffiness above the band. Sleeves that drooped made the bodice bind across the back if they had to reach for something. By designing the sleeves longer and tearing the sleeve pieces 2 1/2 to 3 inches longer than a fitted blouse sleeve, we could create soft fullness above the hands and allow easement in movements, too. I added ruffles to the bottom of the wristband because I wanted to; I just thought it gave the sleeve a finished look. For a time, I cut the bottom of the sleeve in a curve – shorter in front and longer in back like the bottom of a bishop sleeve — with scissors so I could make the back of the sleeves longer and fuller when I gathered it onto the wristband. I don’t do that extra work anymore because it just doesn’t seem worth the effort. And, it looks about the same either way.

**The Tear Dress Yoke.

All of the Tear Dresses made by the costume shop at he Trail of Tears Outdoor drama in 1968 had square yokes without shoulder seams in keeping with the statement that “all pieces were torn because the Cherokees didn’t have scissors.” The neck openings were cut in two was: 1. Some were cut like a “T”; others were cut as a complete circle. All the edges were finished with bias tape. The front opening was cut on-grain in the exact center of the yoke.

Square yoked tear dresses are not comfortable to wear and they look kind of baggy under the arms because the four corners of the yoke get stretch on the bias. All that extra material bunches up under the armpits. A square yoke also never stays in place or evenly distributed front or back: whenever it slides forward, the neck gapes; when it slides backward, it rides up on the neck or it chokes.

For modern women use to well fitting and comfortable clothing where it counts most, the only practical solution was to use fitted shoulder seams that conformed to the slant of the human shoulders. That was achieved by cutting and sewing a separate back and two front yoke pieces with shoulder seams that angled slightly from the neck to the tip of the arm at the top of the arm scye.. The neck opening is cut lower at the center of the front yokes than in the center back yoke.

**Here is my little secret.

I use a commercial blouse pattern to cut my Tear Dress yokes. The shallow slope of the shoulders is perfect for providing ease and neck openings are drafted correctly for either a band collar or no collar at all. Sometime, I lower the center front by a half to three-quarters of an inch to insure that the collar doesn’t lie too high on the throat. Because commercial pattern are standard sizes, I have a collection of various sized from petit to XXL. After determining how deep the yoke should be, I mark the stitching line, add seam allowance and cut the bottom of the blouse patter off and discard it. The yoke is the only piece I cut with scissors when make a Tear dress out of 100 per cent cotton.

**Conclusion

I could go on and on about the tear dress and all of the variations I have seen over the years. I have seen some truly atrocious attempts to make the tear dress by well-intentioned people who sew. I have also seen even worst by people who think they can sew. It should be simple enough After all the seams are all straight.

The worst Tear Dresses are those people try to make for that wicked historical reproduction pattern company that seem to be available at every pow-wow I have ever attended. Tandy leather Company also carried the same line. I have some choice but not printable thoughts about their other garment patterns, too. Especially the men’s Indian and Frontier garb. They should be sued for defective product liability and I would love to see the Cherokee Nation get damages for their fraudulent misrepresentation of the term “Cherokee Tear Dress.” By no stretch of the imagination could a person make a tear dress from the pattern or the instructions. Sadly, I have had to express wonder at some strange fitting garments that were proudly worn by some uninformed, but ethnically prideful Cherokee descendants who trotted them selves down to the Cherokee National Holiday from Kansas City or Des Moines. In not a few cases, it was maddening to find out that they had paid fairly large sums to their local professional dressmakers to stitch their dresses up because they simply didn’t understand the instructions after they had bought the fabric and the pattern.

Sorry souls that they are, I have no heart to point out the inaccuracies of their miss guided intentions to appear historically authentic. My real sympathy goes to the local Cherokees who produce beautifully made tear dress and are willing I make them for far less than the labor and attention to detail deserves.

I have mingled fact with opinion and pray that you are able to distinguish the boundaries between the two. My feeling for the need for first person documentation of our living crafts-people was intensified while I was composing this paper. I had forgotten some of the details of the not so distant past where I was involved in making culture and tradition. I certainly didn’t appreciate my impact in creating precedence while I was doing it. I thought that all I was doing was making a living and doing what had to be done. I have not taken credit for the creation of the tear dress, but after reviewing the sequence of dates and events, I must in all modestly place a few laurel leaves at my own feet. I certainly was instrumental in it’s perpetuation and some modifications. I forgot to mention that the dresses Marion Hagerstand and I made at the drama were used over a period of many seasons because they were well made. They were also borrowed by many individuals and groups to be used for learning and teaching how to make tear dresses. Women that worked in the costume shop at other times while we made tear dresses have used that experience to continue making Tear Dresses for others. I get a sense of real satisfaction when I see their work or am to told that the dress someone is wearing was made by one of that select group of women who once worked with me.

I hope you find this as informative as you had hoped. Moreover, I worry that you will find a modicum of pleasure in reading as I vastly had in writing it. Good luck on your presentation. If you need more, I might be able to dredge up a tiny bit more out of this addled old head.

Your Cherokee brother and friend in Oklahoma.

Wendell Cochran