WASHINGTON, Aug 30 (IPS) – Cyanide and related waste metals — such as those which spilled into the Essequibo River in Guyana earlier this month — have major long-term environmental and health impacts on local people, fish and livestock, according to experts consulted by IPS.

Miners reported dead hogs and fish floating down the Essequibo last week after a holding pond at the Omai gold mine broke and spilt about four million cubic metres of cyanide-laced waste into the river in what is believed to be the biggest such disaster in history.

Environmental activists and scientists say this could be just the beginning. Some compare the disaster to the 1989 Exxon Valdez disaster in Alaska.

Over 11,000 fish were killed along an 80-kilometre stretch of the Lynches River by a similar but far smaller cyanide spill from the Brewer gold mine in South Carolina five years ago.

The Essequibo spill is roughly 100 times greater. Preliminary studies by the Pan American Health Organisation have shown that all aquatic life in the four-kilometre-long creek that runs from the mine to the Essequibo has been killed.

The Omai mine was using a technique called ”cyanide leaching” to extract gold from ore. This process involves spraying cyanide solution on the ore to extract gold. The cyanide waste that is left over is supposed to be stored in lined and covered ponds to prevent contact with local animals and birds.

Invented in 1887 in Scotland, cyanide leaching was first used at Witwatersrand in South Africa. It has gained wide use, however, only during the last two decades when it replaced the older mercury amalgamation process. Leaching can extract greater quantities of gold from the ore.

Popular concern over this technique has focussed on the lethal impact of cyanide. A teaspoonful of two-percent solution of cyanide can kill a human adult. Cyanide blocks the absorption of oxygen by cells, causing the victim to effectively ”suffocate.”

Mining companies like Golden Star Resources of Colorado, one of the owners of the Omai gold mine, insist that cyanide breaks down when exposed to sunlight and oxygen which render it harmless.

Scientific studies show that cyanide swallowed by fish will not ”bio-accumulate,” which means it does not pose a risk to anyone who eats the fish.

But Joseph Maxwell, a Guyanese agricultural chemist at the University of California at Davis, points out that the cyanide solution that seeps into the ground will not break down because of the absence of sunlight.

Other scientists say that if the cyanide solution is very acidic, it could turn into cyanide gas, which is toxic to fish. On the other hand, if the solution is alkaline — as most mine sites are — it does not break down.

Mining advocates insist there have been no reported cases of human death from cyanide spills. But scientists and activists argue that wastes derived from the cyanide leaching process will affect fish and livestock.

”The attitude (is) if you don’t see corpses, everything is okay,” writes Philip Hocker, president of the Washington-based Mineral Policy Centre, in a paper entitled ”Heaps of Gold, Pools of Poison.”

”There is good reason to suspect that a compound as aggressive as cyanide in lethal doses also has serious health effects in long-term chronic exposures at low levels,” he adds.

Art Smith, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) official who was in charge of responding to the Lynches River spill, told IPS that other metals that may have been present in the waste were potentially more dangerous that the cyanide.

”The cyanide concentrations at Lynches was 22 parts per million, which is roughly 1,000 times higher than the levels that we consider dangerous. But copper and iron concentrations at lower levels were probably a bigger part of the problem,” he said.

Guyanese government figures pegged the concentrations of cyanide at Omai at between 25 and 30 parts per million, but they say that this was quickly diluted to three parts per million.

Levels of two parts per million are considered lethal to humans while concentrations as low as five parts per billion can inhibit fish reproduction, which means that the fish population might dwindle over a period of years.

”Yes, there was copper and iron in the solution in Guyana but the levels were too low to be of consequence,” Rick Winters, vice-president of corporate development at Golden Star told IPS. Concentrations cited in company literature ranged from 1.5 to 2.5 parts per million.

Mary Mueller, an environmental scientist who has tested the effect of similar cyanide spills in Colorado, told IPS that copper and sulfates concentrations exceeding one part per million can cause stomach and intestinal problems and kill animals like horses. Lead and mercury can kill humans and also cause stomach problems.

It is these metals that most concern Maxwell, who has been writing letters of complaint to the Guyanese government since June about other proposed gold mines in the country. He believes that processing of gold ore is too dangerous to be undertaken on land that is used for other purposes.

”My guess is that there was mercury at the Omai spill because the entire region was mined for gold by small miners who used mercury. This mercury probably stayed behind,” says Maxwell.

Financially, the worst disaster reported so far has been the failure of the Summitville gold mine in the San Juan mountains of southwestern Colorado. The Summitville mine was operated for six years by Galactic Resources, a Canadian company, until environmental problems forced them to shut.

Cyanide and heavy metal leaks from its operations killed all aquatic life along a 27-kilometre stretch of the Alamosa river. In December 1992, when the extent of the disaster became known, the company forfeited a 6.7-million-dollar bond that it had paid to the state to insure against disaster.

Unfortunately, the remainder of clean-up costs, which have been estimated at over 100 million dollars, will have to be picked up by the government because the company declared itself bankrupt two weeks after the state claimed the bond.

Mueller, who is part of the citizens’ group appointed to oversee the clean-up, says costs have already reached 80 million dollars. No money has been spent yet on cleaning up the impact downstream of the site.

”We are very upset about the fact that no work has been done on the river because we don’t know much about the impact. Our tests show that the water quality on some days is as bad as when the mine was operating. This is despite the fact that the mine shut down three years ago,” she told IPS.

”We don’t have the money for that clean up. At least we can be thankful that we prevented a situation like Guyana from happening here,” says Eleanor Dwight, an EPA official in Colorado.

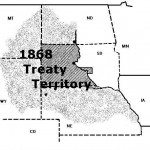

Cyanide-heap leaching in this country began in this country at the Zortman-Landusky mine in Montana in 1979. Four years later, some sheep died from cyanide poisoning after straying into an unfenced area of the mine.

Over a thousand birds were killed at the Wharf Resources mine in the Black Hills of South Dakota when they drank cyanide-laced water at the mine sites. Tom Chapman, a state official, pointed out that the figures did not include fish that may have flown away and died later.