Text of decision on jurisdiction in malt liquor case.

The following is by and from,

Bob Gough, Stu Kaler and Jonny BearCub Stiffarm,

Attorneys for the Estate of Tasunke Witko.

Email: Rpwgough@aol.com

There have been numerous requests for the posting of the Rosebud Sioux Tribe Supreme Court’s memorandum decision in the matter of the Estate of Tasunke Witko (Crazy Horse) vs. G. Heileman and Hornell Brewing companies and Ferolito, Vultaggio & Sons (who also make “AriZona Iced Tea”), so please find the text of the decision attached in ASCII format.

As we have indicated earlier, the RST Supreme Ct ordered a “prompt trial on the merits” on June 15, 1996. On June 26, the Rosebud Sioux Tribe petitioned to join the lawsuit on behalf of the Estate with regard to the claims brought under the Indian Arts and Crafts Act (“…the ultimate in handcrafted malt liquor…”)

On July 22, the brewers filed in federal court for judicial review and an injunction on the Tribal Court, the judge, and the Estate from proceeding in Tribal Court. On August 1, the brewers filed a motion to stay in Tribal Court, citing the alleged “mandate” in National Farmers. On October 9, the Tribal Court granted the tribe’s motion for joinder and denied the stay. The only mandate on the table is that of the RST SupCt. for a “prompt trial on the merits”. The Estate has also filed a motion for summary judgment on the Estate’s rights of publicity under tribal law. Briefs are in the works, with a hearing to be set within 30 days.

We have been honored to serve the Estate and Spirit of Crazy Horse in ways that support the development of tribal courts and Indian law in the protection of the cultural, property and personal rights of Indian people, and have appreciated the interest and support from all those willing to stand with Crazy Horse to the defense of Indian rights.

Much is yet to be done and the battle has become more costly given the additional federal court action and the recent MN Court of Appeals decision requiring either an appeal or new legislation. Contributions in support of these efforts can be made to the Crazy Horse Defense Project (715/425-0004)

Wopila!!

Bob, Stu and Jonny

“SUPREME.DEC”

ROSEBUD SIOUX SUPREME COURT

ROSEBUD SIOUX RESERVATION

ROSEBUD, SOUTH DAKOTA

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

In the Matter of the Estate

of Tasunke Witko, a.k.a. Crazy Horse,

#Civ. 93-204

Seth H. Big Crow, Sr., as Administrator*

of said Estate, and as a member and*

Memorandum representative of the class of heirs*

of said Estate, Opinion Plaintiff/Appellant

vs. and

The G. Heileman Brewing Co., The G..*

Order Heileman Brewing Co.,

d/b/a Hornell Brewing Co.; and Messrs.*

John Ferolito and Don Vultaggio,*

individually and d/b/a/ Ferolito,*

Vultaggio and Sons, *

Defendants/Appellees*

EN BANC before Chief Justice Greaves, Associate Justices Lee, Pommersheim,

Roubideaux, Swallow, and Zephier.

I. Introduction.

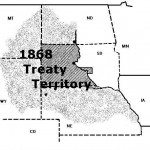

Tasunke Witko, popularly known as Crazy Horse, is a revered nineteenth

century (1842? – 1877) Lakota political and spiritual leader who lived all

of his life within the bounds of the Great Sioux Nation Reservation which

included the present day Rosebud Sioux Reservation. Tasunke Witko was a

person of great moral character who steadfastly opposed the use and abuse

of alcohol products by his people.

Mr. Seth H. Big Crow Sr., a member of the Rosebud Sioux Tribe and a

resident of the Rosebud Sioux Reservation, is a direct descendant of

Tasunke Witko. On March 4, 1993, he filed a petition for Letters of

Administrati on in the Rosebud Sioux Tribal Court and was subsequently

named as the Administrator of Tasunke Witko’s estate on April 12, 1993.

The G. Heileman Brewing Company, Hornell Brewing Company, and John

Ferolito and Don Vultaggio, the Defendants/Appellees herein, are the

manufacturers, distributors, and marketers of various alcoholic (and

non-alcoholic ) drinking products including, but not limited to, the

ornately packaged “The Original Crazy Horse Malt Liquor.” This particular

product has been promoted, distributed, displayed for sale and sold from

on or about March 17, 1992. Other alcoholic (and non-alcoholic) products

of the Defendan ts/Appellees have been manufactured, promoted, and offered

for sale prior to 1992. “The Original Crazy Horse Malt Liquor” has not

been manufactured, advertised or offered for sale in South Dakota or on

the Rosebud Sioux Reservation. Other alcoholic beverages of the

Defendants/Appellees suc has “Old Style,” “Schmidt,” and “Special Export”

are advertised and offered for sale in South Dakota and on the Rosebud

Sioux Reservation. Non-alcoholic beverages of the Defendants/Appellees

such as “Arizona Iced Tea,” “Arizona Mucho Mango Cocktail” and “Arizona

Strawberry Punch Cowboy Cocktail” are also advertised and offered for sale

in South Dakota and on the Rosebud Sioux Reservation.

During the period of March – June 1993, there was written and oral

communication between the parties and other concerned (non-party) Lakota

individuals and groups about the alleged “insult and injury” of

Defendants’ actions and the likelihood of legal action if such activities

of the Defendants/Appellees were not halted.

No mutually agreed upon solution emerged from these various exchanges. As

a result, the Estate of Tasunke Witko filed a lawsuit against the

Defendants/Appellees in the Rosebud Sioux Tribal Court on August 25, 1993.

An amended complaint was filed on September 22, 1993. The complaint and

amended complaint asserted five separate causes of action, namely, the

knowing and willful tortious interference with customary rights of privacy

and respect owed to a decedent and his family, the tortious interference

with Plaintiff’s property right commonly known as the “right of

publicity,” the negligent and intentional infliction of emotional

distress on the heirs of the Estate through acts of exploitation and

defamation, violation of the Indian Arts and Crafts Act, and violation of

the Lanham Act. These claims were asserted – where applicable – under

both tribal and federal law.

The Estate seeks wideranging relief including declaratory and injunctive

relief, money damages, a written public apology, and culturally

appropriate compensation such as “presenting to the Estate one (1) braid

of tobacco, one (1) four – point Pendelton blanket and one (1) racing

horse for each State, Territory or Nation in which said products have been

distributed and offered for sale.” On October 26, 1994, the

Defendants/Appellees filed a motion to dismiss pursuant to Rule 12(b) of

the Rosebud Sioux Rules of Civil Procedure. A hearing on Defendants’

motion was held on June 27, 1994 before the Honorable Stanley E. Whiting,

Pro-Tem Tribal Judge. No testimony was taken at this hearing. The motion

was considered solely on the complaint(s), including affidavits and

exhibits, and Defendants’ motion to dismiss.

On October 25, 1994 the Honorable Stanley E. Whiting granted Defendants’

motion, issued a memorandum opinion, and dismissed the action for lack of

jurisdiction. The trial court’s opinion did not appear to distinguish

between personal and subject matter jurisdiction. The Estate subsequently

filed a timely notice of appeal. The Defendants filed no cross appeal.

Pursuant to Rule 20 of the Rules of Procedure of the Rosebud Sioux Tribal

Court of Appeals, the Court, on its own motion, ordered the appeal to be

heard en banc. Two amicus briefs were properly filed with this Court. On

March 29, 1996, oral argument was heard before the en banc Court sitting at

the University of South Dakota School of Law in Vermillion, South Dakota.

II. Issues.

This appeal raises three significant – and occasionally overlapping –

issues namely;

A. Whether the trial court applied the correct legal standard in

deciding the Defendants’ motion to dismiss;

B. Whether the trial court erred as a matter of law in its analysis

of the issues of territorial, personal and/or subject matter jurisdicti on

as they pertain to Plaintiff’s causes of action sounding in tort,

defamation, and the “right of publicity;” and

C. Whether the trial court erred as a matter of law in its

jurisdictional analysis of the federal statutory causes of action asserted

under the Indian Arts and Crafts Act and the Lanham Act.

III. Discussion.

Each issue will be discussed in turn.

A. Legal Standard for Ruling on a Motion to Dismiss and the

Appropriate Standard of Review.

The proper standard of review on questions of law concerning

jurisdiction is de novo. See e.g. Haisten v. Grass Valley Medical

Reimbursement Fund, 784 F.2d 1392 (9th Cir. 1986). Most unfortunately,

the trial court’s opinion does not articulate or indicate any legal

standard it applied or used to guide its analysis on the motion to

dismiss. This in and of itself likely constitutes reversible error. For

purposes of analytical and conceptual clarity in the future, this Court

provides and sets forth the necessary analysis. The proper standard and

guidance in this regard are found in the case of Lake v. Lake, 817 F.2d

1416 (9th Cir. 1987).

In Lake, similar to the case at bar, the trial court decided the

issue of jurisdiction based on affidavits and other written materials but

without making adequate factual findings. In this case – complicated by

the absence of any legal standard – the analytical groundwork set forth in

Lake is therefore worth quoting in some detail:

The district court decided the issue of its personal jurisdiction

over Taylor on the basis of affidavits and written discovery materials:

thus, the Lakes needed to make only a prima facie showing of jurisdictional

facts in order to avoid the motion to dismiss. Data Disc, Inc. v.

Systems Technology Assocs., Inc., 557 F.2d 1280, 1285 (9th Cir.1977).

Because the court made no findings on the disputed facts, we review the

materials presented de novo to determine if plaintiff has met the burden of

showing a prima facie case of personal jurisdiction. Brand v. Menlove

Dodge, 796 F.2d 1070, 1072 (9th Cir.1986). All factual disputes are

resolved in the plaintiffs’ favor. Id.; Fields v. Sedgwick Associated

Risks, Ltd., 796 F.2d 299, 301 (9th Cir. 1986). Presenting a prima facie

case of jurisdiction, however, does not necessarily guarantee jurisdiction

over the defendant at the time of trial. The district court has the

discretion to take evidence at a preliminary hearing in order to resolve

any questions of credibility or fact that arise subsequent to this appeal.

If such an event arises, plaintiff, being put to full proof, “must

establish the jurisdictional facts by a preponderance of the evidence, just

as he would have to do at trial.” Data Disc, 557 F.2d at 1285.

Therefore, on remand, if there are any subsequent questions of credibility

or fact, the trial court has the discretion to take evidence at a

preliminary hearing in order to resolve same. If such an event arises, as

noted in Lake, Plaintiff must establish the jurisdictional facts by a

preponderance of the evidence, just as he would have to do at trial.

Within the limits of the record before this Court, we will proceed to

analyze the remaining jurisdictional issues engendered by this appeal in

accordance with the prima facie standard in which all factual disputes are

resolved in the Plaintiff’s favor. This analysis will also identify and

apply the appropriate substantive legal standard(s).

B. Jurisdiction.

1. Territorial Jurisdiction.

The Defendants/Appellees contend that the tribal court’s jurisdiction

is territorial in nature and since they never entered the physical confines

of the reservation, there can be no jurisdiction over them for their

activities that took place outside the territory of the reservation. The

argument is seriously misinformed. The law of the Rosebud Sioux Tribe is

clearly to the contrary.

While the Constitution of the Rosebud Sioux Tribe asserts that its

jurisdiction “shall extend to the territory within the original confines of

the Rosebud Reservation boundaries,” this declaration is meant to emphasis

the internal territorial integrity of the tribe’s legal authority as a

matter of tribal law. It is, for example, axiomatic in Indian law that

federal courts have sometimes (perhaps even often) decided the reach of

tribal jurisdiction, at least, in part, on whether the land where the

contested events occurred within the reservation was tribal or individual

Indian trust lands or non-Indian land held in fee. Clearly these land

tenure distinctions within the reservation are not at issue in this case.

The harm, if any, that the Plaintiff Estate suffered was on tribal or

individual Indian trust land within the reservation.

The Rosebud Sioux Tribe does not limit its potential `territorial’

jurisdiction to the crabbed reading suggested by the Defendants/Appellees.

The fact that the tribe has a “long arm” statute set out at Rosebud Sioux

Tribal Law and Order Code=15 4-2-7 indicates the Tribe’s clear intent,

consistent with notions of due process, to assert jurisdiction over

non-residents who, for example, commit tortious acts that have effects

within the reservation.

2. Personal Jurisdiction.

It is this issue that appears to be at the heart of the trial court’s

decision. The trial court’s memorandum decision focuses much of its

attention on the “minimum contacts” analysis required under the due process

guarantee. Yet its analysis is seriously flawed because it does not

articulate any (much less the correct) legal standard applicable to a

motion to dismiss, applies some facts but ignores others without

explanation, and misapprehends and misapplies the appropriate due process

standard. Each of these matters will be treated separately.

a) Motion to Dismiss Standard.

As noted above, the proper standard to apply in the context of a

motion to dismiss is that the Plaintiff needs to make only a prima facie

showing of jurisdictional facts to avoid a dismissal and all factual

questions are resolved in the Plaintiff’s favor. In light of the fact that

all factual disputes are resolved in favor of the Plaintiff, it is both

curious and fatal that some of what would appear to be the most relevant

facts are not even mentioned in the trial court’s memorandum opinion.

b) Relevant Facts.

The Plaintiff made numerous factual assertions in its complaint(s),

affidavits, and exhibits that were not controverted by Defendants and even

if they were, they would have to be construed in favor of the Plaintiff.

However, these assertions were, apparently, simply ignored by the trial

judge. These include, but are not limited to, the following: assertions

that the Defendants continuously advertised and sold other alcoholic

beverages such as “Old Style,” “Schmidt’s,” and “Special Export” in South

Dakota and on the Rosebud Sioux Reservation; that the Defendants

continuously advertised and sold other non-alcoholic beverages such as

“Arizona Iced Tea,” “Arizona Mucho Mango Cowboy Cocktail,” and “Arizona

Strawberry Punch Cowboy Cocktail” in South Dakota and on the Rosebud Sioux

Reservation; that Defendants made at least one telephone call to, and sent

at least one package of allegedly defamatory materials to

Plaintiff/Administrator on the Rosebud Sioux Reservation, and that the

Defendants’ advertising label on each bottle of “Original Crazy Horse Malt

Liquor” specifically exalted and targeted the forum reservation which was

the home of the decedent Crazy Horse and is the home of the

Plaintiff/Administrator. There may be other relevant facts; this is merely

a sampling. At this point, the issue, of course, is not whether these (or

other) facts are ultimately true, but only assuming that they are true (as

we must) do they make out a sufficient prima facie case to withstand a

motion to dismiss? The answer lies in the application of these and other

relevant facts to the applicable “minimum contacts” due process standard.

c) “Minimum Contacts” Due Process Analysis.

Due process exists as an individual guarantee against the federal

government pursuant to the Fifth Amendment, against state governments

pursuant to the Fourteenth Amendment, and against tribal governments

pursuant to the Indian Civil Rights Act of 1968 and any tribal

constitutional guarantee. Normally, the strictures of the United States

Constitution do not apply against tribes. Talton v. Mayes, 116 U.S. 376

(1896). Federal courts have also ruled that the substantive content of the

due process clause and other guarantees of the Indian Civil Rights Act of

1968 need not exactly mirror that of the United States Constitution. See

e.g. Tom v. Sutton, 533 F.2d 1101 (9th Cir.1976) and Wounded Head v.

Tribal Council of Oglala Sioux Tribe, 507 F.2d 1079 (8th Cir.1975). And

while this Court has no doubt that traditional Lakota notions of due

process that provide everyone the opportunity to be heard before making a

decision are met in this case, it is, nevertheless, necessary to also apply

the federal due process “minimum contacts” analysis. This is so because as

the Supreme Court announced in National Farmers Union Ins. Cos. v. Crow

Tribe of Indians, 471 U.S. 845 (1985) the proper extent of tribal court

jurisdiction is ultimately a matter of federal (common) law and therefore

as to matters of jurisdiction, federal standards – including “minimum

contacts” due process analysis – are applicable.

There are essentially two issues involved in construing a long arm

statute. These are whether the intent of the long arm statute is to

maximize its possible jurisdiction and if so, whether such assertion meets

the requirements of due process. The former issue is decided solely by the

local law of the forum and the latter by federal due process analysis.

Helicopteros Nacionales de Columbia v. Hall, 466 U.S. 408 (1984).

As to the former issue, it is clear that the intent of the tribal

long arm statute is that its reach be co-existent with the federal due

process clause. This is in keeping with the modern trend and the tribal

commitment to provide a forum for all wrongs that have impact on

individuals residing on the reservation. The preamble to the tribal long

arm statute which states, in relevant part, the intent of asserting

jurisdiction “to the greatest extent consistent with due process of law”

is unequivocal in this regard. This interpretation of tribal law is not

subject to federal review. As noted by the United States Supreme Court in

Helicopteros Nacionales de Colombia v. Hall:

It is not within our province, of course, to determine whether

the Texas Supreme Court correctly interpreted the state’s long arm

statute. We therefore accept that court’s holding that the limits of

the Texas statute are coextensive with those of the Due Process Clause.

The most recent hallmark decisions of the United States Supreme

Court in the long arm context are Calder v. Jones, 465 U.S. 783 (1984)

and Burger/King v. Rudzewicz, 471 U.S. 462 (1985). Both of these cases

make it clear that it is possible for a forum to assert personal

jurisdiction over a defendant even when he has not physically entered or

carried on business within the forum jurisdiction.

As the Supreme Court noted in Burger King, “The Due Process Clause

protects an individual’s likely interest in not being subject to the

binding judgments of a forum with which he has established no meaningful

`contacts, ties, or relations.'” 471 U.S. 462, 471-72 (citing

International Shoe Co. v. Washington, 326 U.S. 310, 319 (1945)). The

Burger King opinion goes on to emphasize that a potential defendant may

receive the necessary “fair warning” on which to condition jurisdiction if

it has “purposefully directed” its activities at the forum and as a result

it could have or should have foreseen being “haled” into that particular

forum. In addition, the Court emphasized, “Moreover, where individuals

`purposefully derive benefits’ from their interstate activities, . . .

it may well be unfair to allow them to escape having to account in other

states for consequences that arise proximately from such activities.”

Burger King at 473-74. The Burger King Court found the necessary contacts

of the Defendant who never physically entered or carried on business in the

forum state of Florida.

In Calder, the actress Shirley Jones sued the writer of an

allegedly defamatory article about her in California where Ms. Jones

resided. The writer – defendant had never been in California. The Court

found the necessary contacts to justify “in personam” jurisdiction over

the defendant. It emphasized that defendant “knew” that Ms. Jones would

suffer the “effect” of the defamatory statements in the forum state. The

Court also noted that the vehicle for the defamatory article – The

National Enquirer (not a defendant in the case) – had a substantial

circulation in the forum state of California.

If the requirements of Calder and Burger King are integrated and

harmonized, the key questions become did the defendant engage in activities

“purposefully directed” to the forum, did the defendant know the plaintiff

would suffer the “effects” of defendant’s activities in the forum, and was

all of this reasonably foreseeable to justify “haling” the defendant into

the forum’s jurisdiction?

The trial court did not discuss this legal standard, but rather

found no facts to support jurisdiction. The trial court stated,

“[a]ctually, the facts established that Defendant made no contacts with

the heirs of Crazy Horse or with the Rosebud Sioux Tribe Reservation.”

Slip Op. at 13. And again, “[f]urther, there are no contacts whatsoever

by the Defendants with Plaintiff’s [sic] in any manner.” Slip Op. at 14.

These factual conclusions are quite simply erroneous and unwarranted. The

Plaintiff Estate made numerous factual assertions to the contrary (none of

which were even contradicted by the Defendants) which must be assumed to

be true for purposes of a motion to dismiss. Lake at 1420.

A reasonable cross-section of these facts has already been

enumerated. These facts include, but are not limited to, the

advertisement and sale of other alcoholic and non-alcoholic beverages by

the Defendants in South Dakota and on the Rosebud Sioux Reservation, the

making of one telephone call and the mailing of one package of allegedly

defamatory materials by a representative of Defendants to the

Plaintiff/Administrator or his attorney on the Rosebud Sioux Reservation

and that the advertising label on “Original Crazy Horse Malt Liquor”

bottles is specifically directed to the forum.

The trial court provided no explanation for ignoring these facts and

it has therefore committed reversible error. Because the trial court made

no findings on the facts – disputed or otherwise – we review the materials

de novo to determine if Plaintiff has met the burden of showing a prima

facie case of personal jurisdiction. Lake v. Lake, 817 F.2d 1416, 1420

(9th Cir. 1987).

We find that Plaintiff/Administrator has made a prima facie showing.

Defendants are conducting business – albeit only with related non-offending

alcoholic and non-alcoholic beverages – in the forum, and have made

physical – admittedly limited – contact with the forum through the single

telephone call and mailing of package of allegedly defamatory materials to

the Plaintiff/Administrator or his attorney on the Rosebud Sioux

Reservation. These physical and business activities satisfy traditional

“minimum contacts” requirements.

In addition and in support of our conclusion, it is noteworthy to

demonstrate how the Defendants want it both ways. In the advertising label

affixed to each bottle of the “Original Crazy Horse Malt Liquor,”

Defendants clearly exalt and direct their activities to the forum. The

label ornately proclaims:

“The Black Hills of Dakota, steeped in the history of the American West,

home of Proud Indian Nations. A land where imagination conjures up images

of blue clad Pony Soldiers and magnificent Native American Warriors. A

land still rutted with wagon tracks of intrepid pioneers. A land where

wailful winds whisper of Sitting Bull, Crazy Horse and Custer. A land of

character, of bravery, of tradition. A land that truly speaks of the

spirit that is America.”

Defendants demur to this reading claiming that they did not know

there were any living descendants of Crazy Horse, much less living on the

Rosebud Sioux Reservation at the time they began to market and sell the

“Original Crazy Horse Malt Liquor.” While it is true that the Rosebud

Sioux Reservation is not specifically mentioned on the label, it is

clearly subsumed within the phrase “The Black Hills of Dakota . . .

home of proud Indian Nations.” The professed east coast ignorance may well

have been true at the time the product first entered the market, but

certainly it ended when Defendants were informed by the

Plaintiff/Administrator (prior to instigating this lawsuit), other members

of the Lakota Nation, and members of South Dakota’s congressional

delegation and others of their ongoing offensive conduct within the forum.

Conduct, it may be noted incidentally, that has not been discontinued. For

the jurisdictional importance of ongoing activity by a defendant with

notice of the alleged wrongfulness of the conduct at issue, see Beverly

Hills Fan Co. v. Royal Sovereign Corp., 21 F.3d 1558 (Fed. Cir. 1994).

Despite this purposeful activity, Defendants have studiously

avoided the actual marketing and sale of “Original Crazy Horse Malt

Liquor” in Indian country in and around South Dakota including the Rosebud

Sioux Reservation. Given the marketing and sale of similar – but

non-offending – products in the forum, this avoidance appears to be the

most cynical ploy. Defendants exalt and target the forum where it taps a

likely vein of customers, but studiously avoid marketing and sale in the

forum itself because their conduct is potentially offensive and tortious

there. It seems wholly unlikely that the due process clause can be made

to countenance such distortion and manipulation and this Court holds that

it does not.

These marketing activities of the Defendants are “purposefully

directed” to the forum, with notice and knowledge of the potential adverse

“effects” on the Plaintiff/Administrator within the forum. Potential harm

is clearly foreseeable. The actions of the Defendants do not constitute

“mere untargeted negligence.” (Calder at 789.) These facts taken together

clearly meet the requirements of Calder and Burger King. See also Brainard

v. Governors of the University of Alberta, 873 F.2d 1257 (9th Cir. 1989)

in which the defendant was held subject to personal jurisdiction in a forum

where his only contact was to receive two phone calls and respond to a

letter. The defendant never physically entered the forum.

Similarily, in VDI Technologies v. Price, 781 F. Supp. 85 (D.N.H.

1991), the court held for jurisdictional purposes that a party commits a

tortious act within the state when injury occurs in the forum even if the

injury is the result of acts outside the state. This is also the case at

bar. In VDI Technologies, the court found personal jurisdiction over the

defendant based solely on letters defendant sent to plaintiff’s customers

outside the forum because of defendant’s knowledge of the likely harm to

the plaintiff within the forum. Again, this closely parallels the case at

bar. The Defendants were on notice that their ongoing tortious conduct was

causing harm to the Plaintiff Estate within the forum. This case, like VDI

Technologies, is one of purposeful effects, not unintended consequences.

See also Dakota Industries, Inc. v. Dakota Sportswear, Inc., 946 F=2E2d

1385 (8th Cir. 1991). Defendants may not escape accountability in the

very forum they assiduously cultivate when it fits their purposes, but

simultaneously seek to avoid because of the likely harm to accrue there.

The analytical horizon drawn from this line of cases is eminently

reasonable and fully comports with the requirements of due process. We

therefore find that the “minimum contacts” due process requirements – in

the context of a motion to dismiss – are fully met in this case. More

broadly, such a result comports with notions of reasonableness and fair

play that are also embedded in the concept of due process, Sinatra v.

National Enquirer Inc., 854 F.2d 1191 (9th Cir. 1978).

In sum, in assessing personal jurisdiction, the focus is on “the

relationship among the defendant, the forum, and the litigation.” Shaffer

v. Heitner, 433 U.S. 186, 204 (1977). This analysis most often examines

three elements, namely (1) that the nonresident defendant purposefully

directs its activities toward the forum or its residents; (2) the claim

must be one which arises out of or relates to the defendant’s forum related

activities; and (3) the exercise of jurisdiction must comport with fair

play and substantial justice, i.e. it must be reasonable. Haisten, 784

F.2d at 1397. See also Burger King 471 U.S. at 472-76.

As we have seen, the Defendants have purposefully availed

themselves of the forum by advertising and selling other of their

alcoholic and non-alcoholic beverages in South Dakota and on the Rosebud

Sioux Reservation, by placing at least one telephone call to and sending

one packet of allegedly defamatory material to the Plaintiff or his

attorney on the Rosebud Sioux Reservation, and continually targeting the

forum through each label affixed to a bottle of “Original Crazy Horse Malt

Liquor” even after being informed by more than one non-party source of its

offensiveness within the forum and elsewhere on Reservations in South

Dakota.

Jurisdiction, of course, may not be avoided by a lack of physical

contact with the forum state or reservation. This is the central holding

of both the Burger King and Calder cases. Nevertheless, a defendant may

not be haled into a jurisdiction as the result of random, fortuitous, or

attenuated contacts. Burger King, 471 U.S. at 479. In the instant case,

none of the Defendants’ conduct has been random or fortuitous or

accidental. The contact is systematic and ongoing. It was clearly both

proximate and foreseeable that Defendants would be haled into court on the

Rosebud Sioux Reservation. Plaintiff’s claim grows directly out of

defendants’ activities involved in the advertisement, marketing, and sale

of both its offending and non-offending products. It is significant to

emphasize here that the alleged actions of the Defendants do not involve

seeking to market a physically defective product – the classic products

liability situation, – within the forum, but rather a situation where

Defendants are alleged to be intentionally causing harm to the personal or

property (e.g. `right of publicity’) interests at the Plaintiff’s place

of residence and domicile as the result of the manufacturing, sale, and/or

marketing of the “Original Crazy Horse Malt Liquor.”

Finally, the exercise of a forum’s jurisdiction must be reasonable

and comport with fair play and justice. The burden on the Defendants to

litigate in the tribal forum is minimal. They are all national

corporations engaged in extensive interstate commerce. The scope of

Defendants’ resources and the nature of modern transportation and

communication make any ensuing burdens in defending this lawsuit slight.

The reservation forum is likely to be the most convenient for all parties,

while it would be correspondingly difficult both economically and

geographically for the Plaintiff to file his lawsuit in another forum far

away from the reservation.

The local forum is also best situated to provide convenient and

effective relief for the Plaintiff Estate should it prevail at a trial on

the merits. This is particularly significant in light of the fact that

some of the causes of action asserted by the Plaintiff involve questions

of tribal custom and tribal common law that, as questions of first

impression, will not be readily discerned or easily answered in a state or

federal forum at a substantial cultural and geographical remove from the

reservation forum. The reservation forum is also the most efficient forum

for this lawsuit because it has already dealt with the issue of

jurisdiction (which is likely to arise in any forum) and because of its

expertise in evaluating claims grounded in whole or in part in tradition,

custom and/or tribal common law. This is especially true in light of

Justice Marshal’s statement that, “[t]ribal courts play a vital role in

tribal self-government. . . and the Federal government has consistently

encouraged their development.” Such support is particularly appropriate in

this instance where the tribal court is uniquely capable to “provide other

courts with the benefit of their expertise in such matters in the event of

further judicial review.” National Farmers Union, 471 U.S. at 856 (1985).

Finally, the tribal forum has a well justified interest in the lawsuit as

it alleges extensive and pervasive (tortious) harm that has accrued on the

reservation against one of its residents.

3. Subject Matter Jurisdiction.

The trial court also rested part of its decision to dismiss on its

analysis of Montana v. United States, 450 U.S. 544 (1981). Slip Op. at

14-16. The trial court made no distinction in its opinion between

personal and subject matter jurisdiction and the fact that Montana is a

case about subject matter – not personal – jurisdiction. The trial court,

despite observing that Montana was a case involving tribal jurisdiction

over activities taking place on fee lands within the reservation applied

it to events that did not take place on fee lands and also, made a rather

cursory and quite flawed analysis about the applicability of the two

prongs of the Montana proviso. It concluded “that Montana and its protege

[sic] does [sic] not grant jurisdiction to the Tribal court under the

existing factual scenario.” Slip Op. at 16. This conclusion is flat

wrong.

It is the opinion of this Court that Montana is inapplicable to

the case at bar and even if it was, subject matter jurisdiction may

properly be found under both of the Montana exceptions. Since Montana is

often a key case employed both by tribal courts and reviewing federal

courts when assessing the legitimate ambit of tribal court jurisdiction,

some review of that case – what it is and is not about – is in order.

a). Montana v. United States.

Montana v. United States is not a case – despite apparent

conceptions to the contrary in some quarters – in which the Supreme Court

assessed tribal court subject matter jurisdiction as a matter of either

constitutional principles or federal common law. It is rather a case

about statutory construction. In Montana, the Court assessed the

jurisdictional implications of the creation of fee land within the Crow

Reservation as a result of the General Allotment Act and the Crow

Allotment Act. The Court found that Congressional authorization to

alienate tribal lands had the necessary effect of limiting tribal

sovereignty with regard to non-Indian activity on those fee lands. Montana

at 1255-56.

Therefore in the absence of a specific Congressional enactment,

judicial decisions interpreting the reach of tribal court jurisdiction are

properly constrained. See e.g. United States ex rel. Morongo Band of

Mission Indians v. Rose, 24 F.3d 901, 906 (9th Cir. 1994) (Montana

exceptions are “relevant only after the court concludes there has been a

general divestiture of tribal authority over non-Indians by alienation of

the land.”) More broadly, the Supreme Court has noted, “[c]ivil

jurisdiction over such activities presumptuously lies in the tribal courts

unless affirmatively limited by specific treaty provision or federal

statute.” Iowa Mutual Insurance Co. v. LaPlante, 480 U.S. 9, 18 (1987).

Therefore the Montana decision is specifically limited to fee lands. To

extend Montana to non-fee land and beyond the federal statutes involved in

that case is to engage in judicial law making plain and simple. Federal

authority in Indian law is primarily congressional and not judicial in

nature. Courts – including federal reviewing courts – therefore need to

hue to the proper limits of their authority.

In fact, this is exactly what the Montana Court itself did.

When the Court turned its attention from tribal regulation of non-Indian

activity on fee land to regulating the same conduct on tribal (and

individual Indian) land, it did not examine that conduct through the

Montana proviso, but rather summarily observed “The Court of Appeals held

that the Tribe may prohibit nonmembers from hunting or fishing on land

belonging to the tribe or held by the United States in trust for the tribe

and with this holding we can readily agree.” Montana at 1254. If the

Montana court itself did not apply the Montana proviso analysis to non-fee

land, tribal and lower federal courts ought not.

In the case at bar, the harm clearly occurs on individual and

tribal trust land within the Rosebud Sioux Reservation and therefore

Montana analysis is inappropriate. Neither of the parties contends that

there is any other relevant federal statute that potentially bars the

tribal court from asserting subject matter jurisdiction.

It is also pertinent to note that Montana-like analysis is

properly limited to questions of tribal regulatory and legislative

authority and not tribal court adjudicatory authority. The underlying

question in Montana was whether the Crow Tribe could regulate (or

legislate) concerning the right of non-Indians to hunt and fish on

non-Indian fee land within the reservation. The Court answered that the

Crow tribe could not. The Court did not in any way indicate that the

tribal court would not be an appropriate forum to adjudicate a hunting

issue that came up on the Reservation.

The Montana Court did not make the legislative-adjudicatory

distinction. Yet it is this implicit distinction that best explains the

Supreme Court’s subsequent decision in National Farmers Union Ins. Cos.

v. Crow Tribe of Indians, 471 U.S. 845 (1985). In that case, the

Supreme Court held that the tribal court did have adjudicatory

jurisdiction in the first instance to hear a civil dispute, namely a

tortious claim asserted by an Indian student against a non-Indian school

district resulting from a motorcycle accident that occurred on fee land

owned and occupied by a state public school. The Court applied no Montana

analysis. This would seem difficult to fathom but for the fact the case

involved tribal judicial rather than legislative authority. Since the

case at bar involves the question of whether a tribal judicial forum is

available to hear a tort case just like the issue in National Farmers

Union and not whether the tribe can regulate or legislate non-Indian

conduct on fee land which was the issue in Montana, National Farmers

Union’s reasoning is more persuasive and provides yet another reason why

Montana is inapplicable here.

b). The Montana “Proviso”.

Even if Montana were to apply in this case, both prongs of the

famous `proviso’ are satisfied. In Montana, the Court stated that despite

the presumption against tribal (regulatory) authority over non-Indians on

fee land, there might nevertheless be tribal authority:

To be sure, Indian tribes retain inherent sovereign power to

exercise some forms of civil jurisdiction over non-Indians on their

reservations, even on non-Indian fee lands. A tribe may regulate, through

taxation, licensing, or other means, the activities of non-members who

enter consensual relationships with the tribe or its members, through

commercial dealing, contracts, leases or other arrangements. [E.g.,]

Williams v. Lee, 358 U.S. 217, 223. A tribe may also retain inherent

power to exercise civil authority over the conduct of non-Indians on fee

land within its reservation when that conduct threatens or has some direct

effect on the political integrity, the economic security, or the health or

welfare of the tribe. Montana at 1258.

Again, for purposes of emphasis, as discussed above, note the Court’s use

of the word `regulate’ rather than the word `adjudicate’.

The Plaintiff/Administrator in this case alleges, among other

things, that Defendants misappropriated the likeness of `Crazy Horse’ for

their own commercial gain. It is significant to note in this regard that

the trial court specifically recognized a “right of publicity” in the

Plaintiff Estate. Slip. Op. at 11. In other words, the Defendants

failed to enter into a `consensual relationship’ with the Plaintiff for

the use of the name and reputation of `Crazy Horse.’ This case is thus

about, at least in part, the failure (caused by the Defendants) to have a

consensual agreement. It therefore would seem an odd twist to say that

Defendants’ failure to enter into a consensual agreement which gives rise

to the cause of action in the first instance could be used to defeat the

Court’s subject matter jurisdiction. Such reasoning would constitute the

most arid formalism and insofar as the trial court so reasoned, it is

hereby rejected.

Similarly, the trial court – without any analysis that this

Court can discern – concluded that the second prong of the proviso was not

satisfied. Slip Op. at 16. This unsupported conclusion is incorrect.

The ability of the Rosebud Sioux Tribe to protect the `health and welfare

of the tribe’ is directly implicated in this case. It is a touchstone of

tribal `health and welfare’ to be able to provide a forum for the

resolution of alleged harms suffered by tribal members (or any person) on

the reservation. This is particularly, even glaringly, true in the

context of allegations of the tortious interference with, and the

misappropriation of, the image and reputation of a venerated cultural hero

and political and spiritual leader. If the tribe cannot successfully

provide a forum in this dispute of wideranging individual and collective

tribal import, Montana will have indeed run over its fee-lined banks and

inundated the tribal jurisdictional landscape far beyond that which is

justifiable. Confident that Montana was not so intended, we find the

second prong of the process fully satisfied. And we repeat a cautionary

refrain noted at the outset: this appeal and the current posture of this

case are about jurisdiction – personal and subject matter – and the

availability of a tribal forum. We are not concerned at this juncture

about the substantive merit of Plaintiff’s claims or his likelihood to

prevail at trial.

c). A-I Contractors v. Strate.

The Court also feels that it is necessary to make some

observations about the en banc decision of the Eighth Circuit in A-I

Contractors. A-I Contractors involved a non-Indian versus a non-Indian

lawsuit resulting from a car/truck accident that took place on non-fee

land on the Fort Berthold Reservation in North Dakota. In the original

panel decision, the court held (2 to 1) that there was tribal court

jurisdiction. The recent en banc decision vacated the prior decision and

reversed holding Montana analysis applicable even to disputes arising on

non-fee land within the reservation and further found that neither prong

of the Montana proviso was satisfied.

As much of this Court’s discussion suggests, Montana analysis

is inappropriate in this case. And even if it is, both prongs of the

proviso are satisfied. However, very little, if any, of this Court’s

reasoning and analysis appears in the en banc opinion of the Eighth

Circuit and we are confident that if it did, that Court’s decision would

have been otherwise. Regardless of this speculation, this case is clearly

distinguishable from A-I Contractors. This case does not involve only

non-Indian parties, but instead involves an Indian party seeking to

vindicate personal and cultural injuries that clearly transcend the mere

physical harm any `garden variety’ car accident might occasion. The

Eighth Circuit’s wide solicitude when only non-Indian parties are involved

and its correspondingly quite attenuated understanding of apposite tribal

interests in such circumstances are simply not applicable in the case at

bar.

C. Jurisdiction Pursuant to Federal Statutes.

The Plaintiff Estate has also asserted federal causes of action

under the Indian Arts and Crafts Act, 25 U.S.C. 305 et seq. (1994) and

the Lanham Act, 15 U.S.C. =15 1125(a) (1994). Neither of these statutes

limit their jurisdiction to the federal courts. Nor is there any

limitation in tribal law to preclude tribal court jurisdiction as a matter

of local law. The parties do not contend otherwise. In other words,

there are no jurisdictional bars to the assertion of these federal

statutory causes of action in tribal court.

The defenses raised by the Defendants to these two federal claims

are matters of statutory interpretation as to the necessary elements that

make up each cause of action. Each federal statutory claim will be

treated in turn.

1. Indian Arts and Craft Act.

The Indian Arts and Crafts Act was enacted to “protect Indian

artists from unfair competition from counterfeiters.” The purpose of the

Indian Arts and Crafts Act is not at issue in this case. What is at issue

is whether an individual Indian has standing to initiate a lawsuit under

the statute. The Defendants claim that the Plaintiff Estate lacks

standing to bring a claim under the Indian Arts and Crafts Act. This

argument is drawn from a plain meaning of the relevant statutory language

and the supporting legislative history. Specifically, Defendants point to

25 U.S.C. 305(e)(c)(1) as a bar. Defendants allege that the structure of

this section provides standing as follows: “A) by the Attorney General of

the United States . . . on behalf of an Indian who is a member of an

Indian Tribe or on behalf of an Indian tribe or Indian arts and crafts

organization;” or “B) by an Indian tribe on behalf of itself, an Indian

who is a member of the tribe, or on behalf of an Indian arts and crafts

organization.”

Each of these sections permits lawsuits to be filed by

representative parties. In A, the Attorney General is the representative

party and in B, an Indian tribe is the representative party. In both A

and B, the representative body may bring a lawsuit “on behalf of an

Indian” (A) or “on behalf of itself, an Indian who is a member of the

tribe.” There is no additional section that allows an Indian to bring a

lawsuit in his or her own behalf. This reading is particularly reasonable

in that B speaks of “an Indian who is a member of the tribe” (emphasis

added) which clearly refers back to “an Indian tribe” as the

representative party. Without this reading, the word the actually would

be inappropriate and incorrectly used. We are not persuaded that it has

been improperly used, but rather that it harmonizes with the structure of

the standing provisions. There is no ambiguity to be resolved in

Plaintiff’s favor. In addition, as noted in the trial court’s opinion, a

contrary reading would not be consistent with the legislative history of

the Act. Slip. Op. at 19. Finally, the Plaintiff has indicated no case

law suggesting a different result.

2. Lanham Act.

The Plaintiff also alleges a cause of action against the Defendants

based on the Lanham Act. Specifically, Plaintiff claims that the label

affixed to each bottle of “The Original Crazy Horse Malt Liquor”

constitutes false advertising and false association in violation of 43(a)

of the Act as set forth at 15 U.S.C. =15 1125(a). The definitions in the

Lanham Act are to be construed broadly. Smith v. Montoro, 648 F.2d 602,

607 (9th Cir. 1981).

The trial court specifically recognized the Plaintiff’s “right of

publicity” in the name `Crazy Horse’. Slip. Op. at 11. Recognition of

this right, with which we agree, clearly entails the potentiality of that

right being infringed by the `false advertising’ or `false association’ of

the Defendants. At this stage, the Plaintiff Estate has asserted that the

actions of the Defendants involve both `false advertising’ and `false

association’ relative not only to “Crazy Horse” himself but also personal

and tribal beadwork patterns or designs and sacred symbols. Amended

complaint at 15-16. All of these items are potentially subject to

commercial and non-commercial exploitation and loss. That is something to

be developed at the trial on the merits. Neither side has cited to, or

discussed, case law in the context of a motion to dismiss based on lack of

standing under the Lanham Act. The Plaintiff has asserted, without

contradiction, enough to survive a motion to dismiss. The standing issue

may, of course, be revisited at trial.

IV. Conclusion.

For all of the above stated reasons, the decision of the trial court

is hereby reversed in part, affirmed in part, and remanded for prompt

trial on the merits. Specifically, the trial court’s findings as to

personal and subject matter jurisdiction are reversed, as is its dismissal

of the Lanham Act claim. The trial court’s dismissal of the Indian Arts

and Crafts Act claim is affirmed.

HO HE=FEETU YE LO.

IT IS SO ORDERED.

Dated May 1, 1996

Leroy Greaves, Associate Justice

Patrick Lee, Associate Justice

Frank Pommersheim, Associate Justice

Chief Justice, Associate Justice

Ramon Roubideaux, Associate Justice

Michael Swallow, Associate Justice

Diane Zephier, Associate Justice