WASHINGTON, Aug 31 (IPS) – Backers of the two gold mining companies implicated in Guyana’s biggest environmental disaster were also associated with the two biggest cyanide-related gold mining disasters in this country, an IPS investigation has discovered.

On Aug 19, the holding pond at the Omai gold mine, located some 160 kilometres from the north-eastern Atlantic coast of South America broke, spilling some four billion litres of cyanide-laced waste into a tributary of the Essequibo River over a period of five days.

The mine is run by Cambior of Montreal, Canada, and Golden Star Resources of Denver, Colorado, which together own 95 percent of shares in Omai, which produced 252,000 troy ounces of gold last year.

The Guyanese government owns the remaining five percent. Profits from the mine contributed about a quarter of the Guyanese national income of 500 million dollars in 1994, according to Golden Star officials.

Golden Star Resources was controlled by the man who ran the Summitville gold mine in Colorado, site of the most expensive environmental disaster in U.S. history. Cambior bought up a mining company that ran a South Carolina gold mine which was the site of the biggest-ever cyanide spill prior to the Omai disaster.

These two companies also control major mining operations in Burma, French Guiana, Namibia, Papua New Guinea, Suriname and Venezuela.

The man who helped raise the money to create Golden Star Resources was Robert Friedland, a U.S. native who has taken Canadian citizenship. Friedland once owned a company called Galactic Resources that operated the Summitville mine in the San Juan mountains of Colorado.

Summitville, which opened in 1986, introduced a technology called ”cyanide leaching” to extract gold from ore. This process, invented in Scotland and first used in South Africa, involves spraying cyanide solution on the ore to extract gold.

The cyanide waste that was left over was supposed to be stored in lined and covered ponds to prevent contact with local wildlife which can die if they drink the water. Unfortunately, the cyanide solution did not stay in the ponds but leaked through the lining into nearby creeks. By 1990, a 27-kilometre stretch of the Alamosa river was biologically dead.

In September, 1990, an anonymous tip brought the situation to the attention of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Two years later, the EPA seized a 6.7-million-dollar bond posted by the company to begin cleaning up the site.

In November, 1992, Friedland resigned all his positions at the company and declared bankruptcy in December. Exactly one month later, however, the Omai gold mine, Friedland’s next project, began production in Guyana, using the very same technology that had destroyed the Alamosa.

Clean-up operations at Summitville to date have cost 80 million dollars and will run much higher, according to local and EPA officials.

Just as Friedland vanished from Summitville when it was in trouble, he has now taken flight from Golden Star, according to Rick Winters, the company spokesman in Colorado. ”We have nothing to do with him anymore. He sold his shares a long time ago,” he told IPS.

On Oct 28, 1990, just one month after Denver EPA officials were called to the Summitville mine, their counterparts in Atlanta, Georgia, were called out to a similar disaster in South Carolina.

Some 39 million litres of cyanide waste had spilt into the Lynches river after an earthen dam broke at the Brewer gold mine, which also uses cyanide leaching to recover gold. The spill killed an estimated 11,000 fish over an 80-kilometre stretch.

The Brewer mine shut down in January 1993 when Westmont corporation, the mine’s owners, decided that it was no longer profitable. The miners had extracted a total of 180,000 troy ounces of gold in the six years that it operated, about three-quarters of what Omai produced in 1994 alone.

Brewer officials are still at work at the site cleaning up the environmental mess created by the mining operations, which they estimate will cost seven million dollars and not be completed until 1998 at the earliest.

Cambior bought up Westmont in 1993 shortly after Brewer mine shut down. But the South Carolina site was excluded from the deal.

”The disasters in Colorado, South Carolina and Guyana show that cyanide heap leaching just does not work,” says Will Patrick, a field officer for the Mineral Policy Centre, an activist group that tracks mining companies.

Environmental groups have long warned that the owners of Omai have a disastrous track record. Roger Moody, a British activist with the London-based group Minewatch, described Friedland’s past history in an article entitled ”The Ugly Canadian: Robert Friedland and the poisoning of the Americas,” published in the Washington-based Multinational Monitor last November.

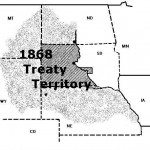

Moody says that Robert Friedland and his brother Eric operate a trust called Ivanhoe Capital, which controls mining operations in Burma, Namibia, Papua New Guinea and Venezuela.

The 1995 Canadian Mines Handbook shows that Golden Star also controls major mining operations in French Guiana and Suriname which border Guyana.

In the Monitor article, Moody says that Friedland convinced the International Finance Corporation, the private finance arm of the World Bank, to sell off part of Galactic’s interests in the Philippines in the early part of the 1980s.

The Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA), one of the World Bank’s newest divisions, also helped the Omai gold mine to get going. MIGA officials told IPS that the agency had re-insured the Omai mine for 49.8 million dollars against nationalisation, civil war or currency risks in 1992.

That re-insurance raises the possibility that, if Guyana seizes the mine in the aftermath of the spill, MIGA may have to pay off the owners.

The World Rainforest Movement (WRM), a British group, has demanded that MIGA be held accountable for not investigating the background of these companies before selling them insurance.

”The World Bank must accept responsibility for the disaster,” says Marcus Colchester of WRM. But MIGA officials say that they have no financial obligations to Guyana, according to officials at their headquarters here.

Five days before the Omai disaster, IPS reported that MIGA had no independent ability to assess the environmental or social risks of mining projects it insured. MIGA officials also said the agency would not take responsibility for damages caused by its clients’ operations.

”Even if there is an environmental disaster, it is not really our problem,” said Gerald West, a senior MIGA adviser. ”It would be a little like appealing to your car insurance company after you were accused of murder,” he explained.

The IPS investigation was provoked by complaints from Indonesian activists that security officials at the Freeport gold and copper mine had massacred indigenous people who had protested the company’s expansion plans. The expansion was the very first project guaranteed by MIGA in 1990.

EPA data shows that Freeport is the biggest corporate polluter in the United States. Investigations into the three U.S. mining companies insured by MIGA in Peru in 1994 disclosed environmentally hazardous practices there as well.

MIGA officials told IPS that they do check the environmental dangers posed by development projects that they insure. This information is given their board of directors, but there are no rules on what should be done with it.

”In the Omai case, we contacted Cambior as well as the Canadian government to find out the situation,” said MIGA’s Walsh. He said that MIGA had not decided what to do with the information.