One of the most widely known and admired persons in the province of South Carolina during the decade preceding the American revolution was Captain John Stuart, a descendant of Scotland’s Royal line. Although an untitled private gentleman, he became the Royal Superintendent of Indian Affairs for the Southern Districts of North America in 1762 largely because of the most amazing example of friendship between an Indian and a white man ever recorded.

This is his story.

Stuart was born at Inverness on September 25, 1718, the third of ten sons born to Bailie John Steuart, a prosperous merchant of that city, and his second wife Christian MacLeod, a native of Skye. Although his father spelled his surname Steuart, John always spelled it Stuart, perhaps this was to emphasize his relationship to the Royal family for it was said he valued honors and titles.

His father was the son of Alexander Steuart, the great-grandson of Walter, 8th Baron of Kincardine, who was descended in a direct line from King Robert II (grandson of Robert the Bruce), through his illegitimate son, Alexander Stewart, the Wolf of Badenoch. John Stuart was also related by blood to the Chiefs of clans Grant, Maclntosh, MacGregor, Cameron and MacLean. He was also related to the Earl of Bute.

At 17 Stuart was sent to London to complete his education then found employment as a clerk for about 3 years at San Lucar de Barrameda, a seaport in Andalusia, on the gulf of Cadiz. He learned to speak Spanish and in 1740 when a war broke out between England and Spain, this ability got him a position with an expedition being sent out under Commodore George Anson to harass Spanish shipping in the Americas. Anson’s expedition circumnavigated the globe and returned to England in the summer of 1744, with a fortune worth 500,000 Pounds taken from Spanish Prizes. It was a difficult, perilous voyage and of the 1,939 men who sailed from England in 1740 only a handful returned. Stuart was one of the fortunate survivors. During the voyage he had been promoted to midshipman and made captain’s clerk of Anson’s flagship.

In the fall of 1745 he became purser aboard a Man-of-War and may have been at sea during the ill-fated Jacobite rebellion. His father was accused, with some justification, of being a Jacobite but there is no evidence his son had such sentiments. If he did he wisely kept them to himself and as many pragmatic Scots were to do, took service with the English government when given the opportunity.In the spring of 1748 Stuart emigrated to Charles Town to go into business with one Patrick Reid, a fellow Scot he had met while Reid was in England on business in 1746.

This was an unfortunate venture for in April of 1754, after several years of declining fortunes, Reid died leaving their failing business and considerable debts to Stuart. By the spring of 1755 their creditors had judgements on everything owned and he was almost destitute. Although bankrupt Stuart remained in Charles Town where he had become accepted and eventually paid off his debts. During this time he married; his wife was named Sarah but oddly enough there is no record of their wedding or the maiden name of his wife is to be found.The first child Sarah Christiana, was born during a visit to England in 1749, she was the first of 3 daughters. Their fourth child was a son, John Joseph, when he became of age young John Joseph expressed a desire to become a soldier. Although disappointed because he wanted his son to follow a career in law, Stuart used his influence to get him a commission as an Ensign in the British army and he became a good one. During a distinguished career he attained the rank of Lt. General and was knighted by the King after a great victory over Napoleon’s army in Calabria. The grateful King of Naples also made him count of Maida.

Stuart was popular in the high living, hard drinking, Charles Town society. He became secretary of the St. Andrews Society, a member of the Library Society, and steward of the Free and Accepted Masons. Described as dignified to the point of vanity he was also a warm hearted, gregarious man, with a pleasing personality. Like most Scots Stuart was fond of socializing with his friends. Consequently he spent many nights at John Gordon’s Inn, reputedly the best public house in America, drinking and singing with his friends until the wee hours and as a result suffered from gout, which almost incapacitated him during his declining years. He held several minor local political offices and in 1755, when war with the French was imminent, Governor Lyttelton commissioned him a Captain in the South Carolina Provincial Militia, with authority to recruit a company to assist in the construction of a fort in the Overhill Cherokee country (west of the Appalachian Mountains, in present day Tennessee). This fort was to protect the homes and families of the Cherokee warriors while they were away fighting the French as English allies.

The fort when completed, in the fall of 1756, just after the formal declaration of war between England and France, was named for General John Campbell, 4th Earl of Loudoun, the British Commander in Chief in North America. The site chosen was near the Cherokee capitol of Chota, a considerable distance into the mist covered mountains and forests of the mysterious Cherokee country. Little did Stuart realize he would experience the most harrowing events of his adventurous life in this remote place. He became a principal actor in one of the most remarkable dramas of Indian loyalty to a white friend ever recorded. It was here he would meet and become the blood-brother of Attakullakulla, (The Little Carpenter), the beloved Peace Chief of the Cherokee Nation, the other principal in that drama. There was a sincere affection between these men that endured for their lifetime.

Although he had no previous experience with Indians Stuart was attracted to their way of life and was readily accepted by the fierce mountain people. A number of Cherokee warriors accompanied General Oglethorpe when he invaded east Florida in 1740 and had witnessed the bravery of the kilted warriors from over the sea, as they battled the Spanish with their deadly broadswords at Fort Mosa. The Cherokee admired the Highland Scots whom they considered fellow warriors. Some purists may be dismayed at this but it is a fact the two races had much in common. Both were mountain people with proud, independent, warrior societies who gloried in a good fight, rough games and reckless living. Both were clan societies which considered loyalty to the clan their first obligation. An Indian’s insistence on vengeance for the killing of a member of his clan was perfectly understood by an 18th century Highlander with a similar custom.

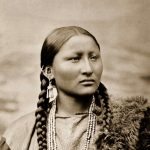

The Scottish Martinmas Fair held each fall, was almost identical to the Cherokee Green Corn Busk, also held each fall. Cherokees passed a newly born child through the smoke of a fire to purify it and the Scots had an identical custom. The Scots were so compatible with the Indians that after 1750 nearly all the traders among the southern Indians were Highland Scots. Because of his ability to get along with the Indians Stuart handled all liaison with them and traded for provisions for the garrison. Captain Demere once suggested Stuart be given command at Fort Loudoun for that reason but nothing was done about this. While serving at Loudoun – according to Cherokee legend – Stuart took a Cherokee maiden, Susannah Emory, as his consort. It is not known if Sarah Stuart ever learned of this. Susannah was the three quarter white, grand daughter of Cherokee trader Ludovic Grant, a transported Jacobite taken at Preston in 1715 and sent to South Carolina to serve a 7 year indenture.

Susannah had a son by Stuart who was called Oo-no-dutu (Bushyhead) as Stuart was , because of his shock of bushy, red-gold hair, typical of the Stuarts. This son, known only by his Indian name, remained among the Indians and married Nancy Foreman, the daughter of a Scottish trader and a Cherokee woman. They had a son who was called Dennis Bushyhead and he became the progenitor of a long line of Bushyheads. ( This is an error as Bushyhead did not have a son named Dennis that I can prove and this is the only mention of him that I have seen. Upon checking with Mr. Nichols in late 1993, a cousin said that he could not find his source at the time and would call back. Jesse was the son of Bushyhead and the father of Dennis….vjj). One of these, Jesse Bushyhead, Stuart’s grandson, became a Christian and was ordained a Baptist Minister. He too remained among his people and accompanied them on the infamous “Trail of Tears”, when the dispossessed Indians were forcibly removed from their home land to Oklahoma in 1838. Stuart’s great, great grandson, Dennis Wolfe Bushyhead was elected Chief of the Nation in 1879 and served with distinction for 10 years.

In the winter of 1756 th fort was completed and Captain Stuart was reassigned to supervise construction of a fort at Port Royal on Beaufort Island, just south of Charles Town. In the summer of 1759, as reports of trouble with the Cherokees began, he was ordered back to Loudoun with a party of 60 artillerymen to reinforce the garrison. The incidents which precipitated the tragic Cherokee War of 1759-61 are too numerous and involved to be related here. Let it suffice to say a study of these should convince any reasonable person the Cherokees, loyal allies of England since 1730, were provoked into this war by the insufferable acts of British soldiers and certain Virginia ruffians.

Colonel James Grant, of the 77th Regiment, whose name became synonomous with destruction to the Cherokees, summed up the situation with typical Scottish brevity in a report to General Amherst in 1760. “The Cherokees are more sinned against than sinning, they sincerely desire peace but know not how to get it”.

When Stuart first arrived at Fort Prince George in Cherokee country of western South Carolina, he met Ouconnostotah, the Cherokee War Chief, who was enroute to Charles Town with a delegation of 28 Chiefs to speak to the Governor. They hoped by this to avert a full scale war which might destroy their people. It is a measure of Stuart’s popularity with the Indians that the fierce War Chief gave him an escort of warriors to guide him safely to Loudoun. Soon after Stuart returned to Loudoun the garrison was shocked to learn the peace delegation had been treacherously made hostage by Governor Lyttelton and imprisoned at Fort Prince George. Ouconnostotah and two other Chiefs were later released to carry Lyttelton’s demands for peace to the Nation but the remaining hostages were murdered by the garrison to avenge the killing of their commander. This man who had led a party of drunken officers from the fort into Keowee Town and invaded the home of two Cherokee women to rape them, was lured out of the fort by Ouconostotah on February 16, 1760, and shot to death by hidden marksmen to pay for this crime.

Attakullakulla had done all he could to avoid a war but he was ignored. The murder of the hostages was the signal for widespread raids upon the frontier settlements of Georgia, the Carolinas and Virginia. South Carolina was the hardest hit and as hundreds of terrified refugees fled before the enraged Indians her frontier was pushed back over a hundred miles and the government at Charles Town was powerless to prevent this. Prince George and Loudoun were besieged and every trail in or out of the Indian country was watched to prevent anyone from leaving or supplying the garrisons.

The Indians began firing on Fort Loudoun on March 2Oth but stopped after a few days to save their ammunition. They knew the garrison would soon run out of food and be forced to surrender. In February of 1760 a desperate Lyttelton sent an urgent message to General Amherst at New York asking for regular troops to subdue the Cherokees and relieve Fort Loudoun. Amherst responded by sending Colonel Archibald Montgomery, son of the Earl of Eglinton, with 1200 tough, seasoned, Scottish soldiers of the First Regt. (The Royal Scots), and the 77th Regiment (Montgomery’s Highlanders), to Lyttelton ‘s assistance. Handicapped by Amherst’s order to conduct a speedy campaign to punish the Cherokees and return to New York as quickly as possible, Montgomery accomplished little. He burned a few villages and killed a few Cherokees but most of the warriors escaped into the hills, more angered than intimidated. With smallpox breaking out among his men Montgomery was reluctant to cross the mountains to relieve Fort Loudoun so he invited the Cherokee leaders to come to Fort Prince George and make peace. He demanded they supply Fort Loudoun and Captain Stuart be allowed to accompany Attakullakulla to negotiate the terms. There was no response for the Indians feared anyone they sent would be killed, just as the hostages were killed.

Montgomery next attempted to relieve Loudoun but his force was severely mauled in an ambush at Etchoe Pass, shortly after leaving Prince George. He retreated to the fort and convinced that he could not cross the mountains to Loudoun burdened with so many sick and wounded, he returned to Charles Town, where he loaded his men aboard his transports and returned to New York. His retreat was the death knell for Loudoun and the garrison despaired as triumphant Indians pranced before the walls, Boasting of Montgomery’s defeat. Loudoun was under siege over four months and by August the condition of the garrison, and their families was desperate.

Several men deserted, preferring to risk death by torture to certain starvation. On June 29th Captain Paul Demere was able to send out a message which reported: “The garrison is miserable beyond description, feeling they are abandoned by God and man without hope of relief and without even horse flesh upon which to subsist. After that there was silence.

On August 6th the officers met and decided to ask for terms. The following day Captain Stuart and Lt. James Adamson negotiated an agreement with Ouconnostotah at Chota to surrender the fort. Two key provisions of the agreement were: 1st, That the garrison of Fort Loudoun march out with their arms and drums, each soldier having as much powder and balls as their officers shall think necessary for the march and what baggage he may choose to carry. 2nd, that the garrison be permitted to march for Virginia or Fort Prince George , as the commanding officer shall think proper, unmolested, and that a number of Indians be appointed to escort them and hunt provisions for the march.

On August 9th the English flag was hauled down and 100 men, 60 women and a number of children, escorted by Ouconnostotah and a large party of Indians, left the fort to make for Prince George, 140 miles away. Weak from starvation they were able to walk only 15 miles along the Tellico River before stopping to rest. During the night their escort slipped away and early the next morning guards reported Indians hiding in the bushes around the camp. John Stephens, a survivor, gave an eyewitness account of what occurred next: “After the beating of reveille, while (the soldiers), were preparing to march, two guns were fired at Captain Demere, who was wounded by one of the shots…..

Lt. Adamson who stood beside him viewed the two Indians, returned their fire and wounded one …the war whoop was then setup…. and volleys of small arms fire with showers of arrows poured in….. from (700) Indians, who as they advanced surrounded the whole garrison and put them into the greatest confusion… they called to each other not to fire and surrendered. Some endeavored to escape but….the Indians rushed upon them with such impetuosity that it was in vain. By this time all the officers, except Stuart (who was during the assault seized by an Indian, perhaps by the Little Carpenter’s arrangement and carried to the other side of the creek), with between thirty or forty privates, and three women were killed, “Captain Paul Demere, whom the Indians disliked intensely suffered a cruel death. He was scalped while still alive and forced to dance while being beaten with sticks for his tormentor’s amusement. When they tired of that his arms and legs were chopped off and his mouth stuffed with dirt. They taunted him as he lay dying by saying: “You English want land, we will give it to you”.

Stuart was hurried back to Loudoun where Attakullakulla gave every thing he owned, except his loin cloth, to purchase him from his captor. His relief was short for he learned Ouconnostotah intended to force him to use the cannon taken at Loudoun against Fort Prince George, the alternative was a hideous death by torture. Somehow he persuaded Attakullakulla to help him escape and that loyal friend at the risk of his standing and his life got him away from the Indian camp by a subterfuge and led him across the mountains to an advance party of an expedition enroute from Virginia to relieve Fort Loudoun, Somehow they persuaded Colonel Byrd who led the expedition, to allow them to negotiate a truce with the Cherokees and hopefully get them to release any prisoners who remained alive. Byrd allowed them to try and Attakullakulla returned to Chota for that purpose.

Although opposed by French emissaries, he arranged a truce that ended the fighting until March of the following year and saved the lives of many of the prisoners. Byrd got credit for this but it was Stuart’s idea. Stuart returned to Charles Town on Christmas Day of 1760 and found his experience had made him famous. When the Provincial Assembly met on January 21, 1761, Governor Bull recommended he be compensated for his personal losses and extraordinary expenses incurred in in the public service and rewarded for his devotion to duty. The Assembly awarded him 1550 pounds Provincial currency and recommended him to the Governor as a person highly deserving promotion in the provincial service.

The Cherokee war was not ended by the truce for General Amherst was infuriated to learn British soldiers had surrendered their fort to Indians, whom he despised. He immediately dispatched 2000 men of the same regiments who fought in Montgomery’s campaign, to chastise the Indians and wipe out the insult to British prestige. Commanding the force was Colonel James Grant, who was Montgomery’s aide in the previous campaign. Grant was an experienced officer who planned his campaign well, it was short, ruthless and decisive. After defeating a large Cherokee force at Etchoe Pass, where Montgomery had been ambushed, he burned the homes, crops and livestock of the Middle Towns which had never before been invaded and thousands of Indians were driven into the hills, destitute and starving. Grant then returned to Fort Prince George and summoned the Cherokee leaders to a peace conference.

Attakullakulla, and eight other Chiefs responded. They were anxious to end the war but a condition that four Chiefs from the four parts of the Nation be executed before the garrison as an example caused consternation. Atakullakulla told Grant they could not order such a thing and asked to be allowed to speak to Lt. Governor Bull concerning this demand. Grant wisely allowed him to do so, Stuart, who had not been involved in Grant’s campaign accompanied Atakullakulla and took part in the negotiations. Fortunately Bull was no Lyttelton, he realized the war had been unnecessary and was anxious to make peace for the good of his province. Advised by Stuart, he and Attakullakulla negotiated a treaty which eliminated the provision calling for the execution of four Chiefs and the Cherokee War was over. This was reported by The South Carolina Gazette on Sept. 23, 1761: “On this day Attakullakulla had his last public audience, when he signed the treaty of peace and received an authenticated copy under the great seal. He earnestly requested that Captain John Stuart might be made chief white man (Indian Agent) in their nation. `All the Indians love him,’ he said,’ and there will never be any uneasiness if he is there’. His request was granted.”

Attalcullakulla meant to secure the post of provincial Indian Agent for his friend but better things were in store for Stuart. Thomas Boone, the new Govenor, impressed by his influence with the Indians suggested Amherst recommend him to succeed Edmund Atkin, the first Southern Superintendent who had recently died. Amherst did so and on January 5, 1762, Stuart was appointed Royal Superintendent of Indian Affairs for the Southern Districts of North America. Stuart held office for 18 years, during which he had a harmonious relationship with the Commanders in Chief and Ministers under whom he worked. At a time when many Roya] officials considered their office mainly as a means to advance their own fortunes.

Stuart’s tenure was one of the few bright spots of the English administration of her American colonies. He was a consummate diplomat and truly devoted to his savage charges, their welfare was always his foremost concern. The southern Indians in turn loved and trusted their “Beloved Father,” a title of great respect given him by the Cherokees. Stuart was criticized by some because whenever possible he appointed fellow Scots as his deputies. At least two of these were relatives, his brother Henry and his cousin Charles Stuart. Stuart’s life changed dramatically after the confrontation at Lexington in the spring of 1775.

Some of his policies had made enemies in Charles Town and as the revolutionary fever grew some of these accused him of being the English Ministry’s instrument in a plot to rouse the Indians and incite a slave revolt. This was totally unfounded but because of his well known loyalty to the English government and his great influence over the Indians, many believed it. Warned by friends of a plot to seize him he fled to St. Augustine in the summer of 1775. In 1776 he established his headquarters at Pensacola where he reluctantly followed orders from General Gage to use the Indians to distress the American Rebels.

Stuart did not survive the revolution. Worn out by years of failing health he died of consumption at Pensacola on March 21, 1779. Sir Henry Clinton, the Commander in Chief, supplied the old Highlander with a fitting eulogy in a report to Lord Germain: “The loss of so faithful and useful a servant to His Majesty is at all times to be regretted, but at this critical juncture is most sincerely to be lamented. “The Cherokees did not record their reaction to this death but it is certain their “Beloved Father,” was greatly mourned.

In the fall of 1760 during the truce arranged by Stuart and Attakullakulla, Ouconnostotah sent The Mankiller of Nequasee and the Raven of Chota to smoke the peace pipe with the officers of Fort Prince George. He allowed Cherokee women to barter fresh meat and vegetables with the men of the garrison and as a special treat sent a piper captured during Montgomery’s campaign to entertain the garrison, whom the Indians called: “The Scotch Company.” S.C. Gazette, Oct. 18, 1760.

Several authorative sources tell us Stuart came to North America with General Oglethorpe, or the Scots who emigrated to Georgia to found the Darien settlement in 1736, but they are mistaken. A petition by Stuart himself, to the Board of Trade, dated Sept. 23, 1766, gives the date of his emigration as 1748 (British Public Record Office, Colonial Office papers 5/67). The name Charles Town has been used in this narrative because it was used during that period. This was changed to Charleston by an act of the South Carolina General Assembly on August 13, 1783.