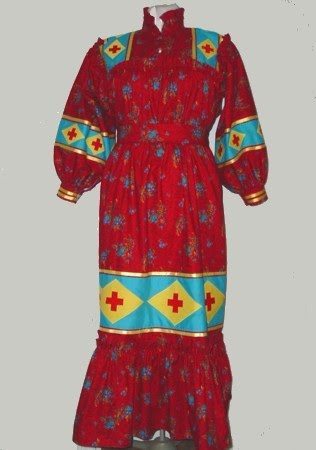

“The Official Women’s Dress Of The Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma”

A Fact Sheet Written by Wendell Cochran,

Cherokee Master Craftsman and National Living

Treasure in the Area of Traditional Clothing.

The Cherokee Tear Dress is the official tribal dress for women of the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma by proclamation of the National Council. The Cherokee Nation is the only tribe to my knowledge to legislate a specific style of clothing as the official tribal dress. The Cherokees of North Carolina have a completely different style of dress.

A Cherokee Tear Dress must have these basic elements of construction and design:

All pieces of the dress must made of squares and rectangles; The bodice must be gathered onto a shoulder yoke and open up the front;

There must be square gussets under the arms where the sleeves attach to the bodice;

There must be a stand up ruffle where the lower bodice and sleeve are attached to the yoke and where the skirt flounce is attached to the upper skirt panels;

There must decorative fabric bands at certain places on the dress, which are over each shoulder of the yoke, around each sleeve, and around the upper shirt just above the flounce.

A woman may choose a number of variations that reflect her own sense of style:

Any kind of fabric is acceptable as long as it can be gathered softly (cotton calico, prints and solid, any type of fabric weave including broadcloth, crepe or chiffon); A choice of skirt length, either ankle or floor length for ceremonial events, or below the knee length for social, formal and daytime wear. Stomp dancers usually choose a shorter length. A choice of sleeve lengths — elbow, three-quarter, or wrist lengths is acceptable.

The decorative bands may be plain and solid, have cut-out and/or appliqued motifs of a combination of square and triangle shapes, or embellished with beaded or embroidered motifs of trailing vine-like designs that are consistent with the traditional Southeastern Woodland tribes. The neck opening may be finished with a stand-up band collar, a round neck with no collar or finished with a ruffle, or a plain faced square neck opening.

Every contestant who enters the annual “Miss Cherokee” contest must wear a Tear Dress of any variation of the above style choices, as long as it is cut accurately from squares and rectangles and has a square arm gusset under the arm. The Tear Dress has been a contest requirement since 1969. Miss Suzy Coon was the first girl to compete and be crowned as Miss Cherokee in a Cherokee Tear Dress.

The first official tear dress was made for and worn by Virginia Stroud during her reign in the titled position as “Miss Indian America” 1969. (More about the origin and selection of the prototype dress further down in this fact sheet.)

The word “tear” is pronounced as in “rip and tear”, not tear as in the act of crying or in Tail of Tears. No one can remember who named it the Tear Dress. The name is onomatopoeia; it describes how the pieces of the dress are cut during construction. The original dress was constructed of simple shapes of squares and rectangles and each piece was torn across the grain of the fabric and not cut with scissors.

The dress is a basic shirt-waist style. The bodice top (the old fashion term is waist) is attached the skirt by means of an inset waistband and closes up the front with buttons, much like a man’s shirt. To provide ease, shape and form, larger pieces are gathered and sewn onto smaller pieces of the garment. Historically, this style of shirt-waist dress was worn by working class women — trades people, farmers, crafters, etc., who did not have the luxury of having a personal attendant to help them get dressed each day like the privileged class who dressed in stylish, form fitting garments that were fastened up the back with rows of hooks and eyes. This was the type dress that was made at home, either by a member of the family, or by the neighborhood seamstress.

The dress is practical for two reasons:

The fullness of the gathered bodice and skirt gave the wearer freedom of movement to do the labor of daily work chores, and the one piece construction allowed women to bend and stretch with out fretting with the problem of keeping a waist tucked in or hooked to a skirt. Making a Cherokee Tear Dress requires a medium-to-advanced knowledge of garment construction and sewing skills. A well fitting dress requires taking accurate measurements, a fair understanding of the sequence of steps needed to cut, sew and finish the dress, and a lot of patience. There are a few commercially printed tear dress patterns now available on the market, but none give complete instructions or are self-explanatory to the novice tear dressmaker.

Measurements:

Every tear dress is one-of-a-kind original creation and is usually made to fit the individual.

The primary measurements required are:

Length of the bodice from shoulder to waist (front and back); Opening of the front from neck to waist;

Length of skirt from waist to finished hem;

Length of sleeve from tip of the shoulder to finished sleeve band;

Width of shoulder yolk across the back from tip of the arm to tip of the arm;

Waist and finished waistband;

Sleeve band at the finished length of the sleeve. Bust and Hip measurements are not too important except if the woman is extremely busty or has large hips in proportion to her waist. You then have to allow extra fullness to the width of the pattern pieces to in the front lower bodice and the skirt.

Cutting:

Every piece of the original Tear Dress was a torn square or a rectangle. At the time the dress was made, cotton goods on the bolt were generally only 18 or 24 inches wide, perfect widths for the pieces of a Tear Dress. 100 percent cotton materials are easy to tear across the grain from salvage to salvage. Modern day cotton/polyester fabrics must be cut, otherwise they leave a ragged, puckered edge.

Twenty-four inch fabric, which was the standard for all cotton prints and calicos up until the early 1960’s, was the ideal width for making a tear dress. For an average person, sleeves could be made twenty-four inches wide; a skirt could be made of three panels (72 inches) giving a seam opening down the front of the skirt; the lower back bodice piece and the two front bodice pieces (torn length ways in half) could each be one width of fabric; the 18 inch square yoke could be cut from one width — the remaining six inches piece would be used for sleeve bands, neck bands or front/placket opening facings. Modern day fabrics are now between 42 to 45 inches wide and require making a cutting guide to plan how to cut the widths and the length of each piece to approximate the proportions of the original dress.

The True History of the Cherokee Tear Dress.

This story may seem shocking and little sad to some who are romantically inclined to the modern myth about the Tear Dress. The myth is that our women wore this style of dress at the time of the Trail of Tears in 1838-39. That is not true for two reasons.

First of all, Cherokee never had a traditional style of dress that was unique or ethnically different than any other tribe in the hot and humid Southeastern United States. The clothing of both sexes, as described by the very earliest European adventurers, was primitive and scant, covering mostly their private parts, and made of mostly animal hides and furs. They did use a rudimentary form of finger weaving and netting to make sashes, belts and rope. Loom weaving technology, which would allow them to make piece goods, was not available until the opening of the frontier to missionaries, the Moravians in particular.

Once the Cherokees were able to weave their own fabrics and/or obtain commercially made trade goods from American mills or from England they quickly abandoned the labor-intensive leather buckskins in favor of the softer, cooler and readily available woven fabrics. The only cloth clothing they had for patterns were those worn by white traders, inter-married whites and later, the Moravian and other Christian missionary ladies.

The clothing they made was fashioned on the type of clothing they were taught to make plain, simple and utilitarian. Frontier fashion was nothing like those seen in picture books and paintings of the ladies in eastern sea coast cities such as Boston, Philadelphia or New York. The second reason that the Tear Dress could not have been worn at the time of the Trail of Tears is because the style is completely wrong for the period. Women’s fashions of every historical period have a very definite silhouette, related primarily to the rise and fall of the waistline and the shape and size of the skirt.

In the late 1830’s, the period of the beginning and the end of the Trail of Tears episode, women of fashion in the cities along the eastern seaboard were wearing garments that costume historians call late Empire, Romantic period, or Early Victorian. These styles of women’s dresses had high waists, bell shaped skirts, which compared to the previous period when skirts were exceedingly wide and heavy, were very narrow (dress makers were just beginning to perfect the art of cutting gores) and had short puffy sleeves which eventually evolved into elaborately wide and full bell shapes. Fashion on the interior did not follow those changes as quickly. Some historical experts estimate that for every 100 miles west, fashion lapsed at least five years behind the times. The Tear Dress is definitely a style that came into fashion at a later date.

There is one painting extant of a Texas Cherokee couple which shows the woman wearing a most definite “Empire” style gown – high waist, bell shaped skirt and short puff sleeves. Whether this painting was executed on site with real Cherokees as models, thus recording a moment in time, or was finished by the artist at a later time, and using another model in city-fied clothing. It was not uncommon for artists to use substitute models when painting Indian subjects.

When we were “discovered” by the Europeans, we were wearing leather garments and had no knowledge of making woven fabrics suitable for making garments. We did however have the knowledge of making a limited amount of a primitive form of weaving or twining in order to make small articles like belts and fishing nets.

Once we were introduced to white man’s trade goods and other forms of his civilization, including his type of clothing, we readily and quickly adopted the used those goods and materials without hesitation. Cloth was one of the first items to be brought in and traded to the native people. Moravian missionaries introduced weaving to the Cherokees as a means of civilizing the naked savages. Many Cherokee became accomplished weavers, as proven by the federal census that listed household members by name and each one’s trade or skills, including the number of looms and the number of weavers among the Cherokees. Christian missionaries insisted that Indian converts dress appropriately when attending church services or school. That meant that Cherokee women had to cover their bare breasts and naked legs with dresses prescribed by the white missionaries. They were taught how to sew those garments by the missionary wives and teachers. The style was simple and plain.

The most common style that comes to mind is the one called the Mother Hubbard — a shift-like garment that looked very similar to a modern day nightgown. It was the style of choice introduced to nearly all Indian tribes in schools, reservation churches and to household servants throughout the 1800’s. The Hawaiian Muumuu is the perfect example of the Mother Hubbard that was adopted and is now identified as a traditional tribal dress.

Because the Cherokees quickly adopted the lifestyle of the early white settlers, they, along with the other four major tribes of the Southeast, became known as the “Civilized Tribes”. We mimicked the dress and habits of the surrounding white communities and establishments. Some individuals maintained a type of mixed wardrobe of both native and white. Some paintings show that there were groups that continued to dress in the old Cherokee way until the late 1840’s after the Cherokees had settled into their new homelands in Indian territory. George Caitlin’s sketches (c. 1830’s at Ft. Gibson) show examples of Cherokee Indian women wearing leather garments during the early years of settlement in the newly opened Indian Territory prior to the full influx of Cherokees on the Trail of Tears. One memorable sketch shows a Cherokee woman in leather wearing a paisley shawl.

Between 1839 and the 1860’s at the beginning of the Civil War, the period in which the tribe established public schools, seminaries and a formal government, the affluent Cherokees had abandoned all forms of their ethnic style of dressing. After the Civil War, a few traditionalists, who were perhaps economically the poorest, continued to retain one style of ethnic clothing, the Hunting Jacket. The basic design for the jacket was adapted from a type of popular casual garment worn by white men, called a Banyon. There is a picture of Samuel Wooster wearing a Banyan. A few rare old photographs still exist that show men wearing a native–made hunting coat.

One can surmise that these garments continued to be worn because they were easy to make at home out of store bought trade cloth or fabric they wove at home. No doubt the women in those families also wore home made clothing that was functional yet simple in design and construction. There simply are no photographs to prove this as fact or what the dresses may have looked like. Perhaps they were simple shifts or A-line type dress that were made somewhat like the old leather deer skin garments, i.e. Straight panel front and back and sewn across the shoulders and down the sides with an opening for the head and arms, much like the plains Indians’ pow-wow dresses.

Cherokee women had no such traditional tribal dress. There was no real reason for them to cling to any particular style because they few opportunities to interact with other tribes like we do today with our pow-wows and inter-tribal events. Any style of clothing that a Cherokee woman might wear at any particular time was discarded once the dress wore out and merchants introduced new fashion ideas and new types of fabrics.

The origin and adoption of the modern day Cherokee Tear Dress. The garment we call the Cherokee Tear Dress came about to fulfill the needs of a particular situation and had more to do with embarrassment than it had to do with tribal pride or tradition. The situation arose in 1968 when a young Cherokee woman, by the name of Virginia Stroud, was chosen as “Miss Indian America”. She had competed and was crowned in a Kiowa buckskin dress she had borrowed from a college friend.

W.W. Keeler, who was the appointed Cherokee Chief at the time, was approached by a group of Cherokee women about Virginia Stroud’s official wardrobe. They felt it was unacceptable for a Cherokee women who was suppose to be representing the Cherokee people in the public eye was appearing at public events dressed as a Kiowa. Chief Keeler agreed and appointed a committee of Cherokee women to find something more appropriate for Miss Stroud that would reflect the Cherokee’s eastern woodland traditions, history and style.

They could not find an established precedence in Oklahoma for a traditional tribal dress. The answer they decided could only be found someplace in North Carolina, Georgia or Tennessee. The ladies mounted a serious search for a record of a dress design that would be uniquely Cherokee and acceptable by Chief Keeler. They did not want to simply copy or adapt any other tribe’s style. And they did not want the dress to look anything like the Plain’s Indian dress. They also wanted the dress to be historically correct and if a dress could be found, it had to be documented.

Part II contains eyewitness accounts of the prototype of the first Miss Cherokee Tear Dress, how and by whom it was discovered, how it was copied and who made the first original copy, and how the pattern and construction methods were perfected. Names of those involved will be given; some of them are still alive, as is Miss Virginia Stroud who now lives in Tahlequah, OK. She still has that original dress along with the original crown and white turkey feather cape she wore during her reign as Miss Indian America.

We’d like to thank our friends at https://pokercasinodownload.com for sponsoring this page. Read their review of the Bovada Poker download which is licensed by the Kahnawake Gaming Commission in the Mohawk Territory of Kawhawake in Canada.

We also recommend the Americas Cardroom download which offers free games.