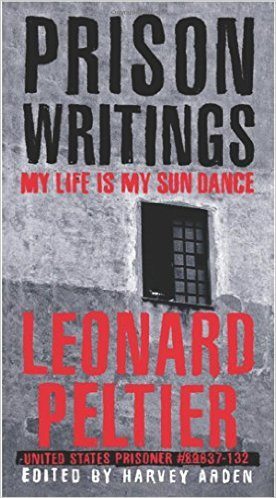

THE TIME HAS COME for me to set forth in words my personal testament — not because I’m planning to die, but because I’m planning to live.

This is the twenty-third year of my imprisonment for a crime I didn’t commit. I’m now fifty-four years old. I’ve been in here since I was thirty-one. I’ve been told I have to live out two life-time sentences plus seven years before I get out of prison in the year 2041. By then I’ll be ninety-seven. I don’t think I’ll make it.

My life is an extended agony. I feel like I’ve lived a hundred life-times in prison already. But I’m prepared to live thousands more on behalf of my people. If my imprisonment does nothing more than educate an unknowing and uncaring public about the terrible conditions Indian people continue to endure, then my suffering has had — and continues to have — a purpose. My people’s struggle to survive inspires my own struggle to survive. Each of us must be a survivor.

I ACKNOWLEDGE my inadequacies as a spokesman, my many imperfections as a human being. And yet, as the Elders taught me, speaking out is my first duty, my first obligation to myself and to my people. To speak your mind and heart is the Indian Way. In the Indian Way, the political and the spiritual are one and the same. You can’t believe one thing and do another. What you believe and what you do are the same thing. In the Indian Way, if you see your people suffering, helping them is an absolute necessity. It’s not a social act of charity or welfare assistance; it’s a spiritual act, a holy deed.

I HAVE NO APOLOGIES, ONLY SORROW. I can’t apologize for what I haven’t done. But I can grieve, and I do. Every day, every hour, I grieve for those who died at the Oglala firefight in 1975 and for their families — for the families of FBI agents Jack Coler and Ronald Williams and, yes, for the family of Joe Killright Stuntz — a 21-year old brave-hearted Indian whose death from a bullet at Oglala that same day, like the deaths of hundreds of other Indians at Pine Ridge at that terrible time, has never been investigated. My heart aches in remembering the suffering and fear under which so many of my people were forced to live at that time, the very suffering and fear that brought me and the others to Oglala that day — to defend the defenseless.

And I’m filled with an aching sorrow, too, for the loss to my own family because, in a very real way, I also died that day. I died to my family, to my children, to my grandchildren, to myself. I’ve lived out my own death for nearly a quarter of a century now.

Those who put me here and keep me here knowing of my innocence can take grim satisfaction in their sure reward, which is being who and what they are. That’s as terrible a reward as any I could imagine.

I know who and what I am. I am an Indian — an Indian who dared to stand up to defend his people. I am an innocent man who never murdered anyone nor ever wanted to. And, yes, I am a Sun Dancer. That, too, is my identity. If I am to suffer as a symbol of my people, then I suffer proudly. I will never yield.

IF YOU, THE LOVED ONES of the agents who died at the Jumping Bull property that day, get some salve of satisfaction out of my being here, then at least I can give you that, even though innocent of their blood. I feel your loss as my own. Like you, I suffer that loss every day, every hour. And so does my family. We know that inconsolable grief. We Indians are born, live and die with inconsolable grief. We’ve shared our common grief for twenty-three years now, your families and mine, so how can we possible be enemies anymore? Maybe it’s with you and with us that the healing can start. You, the agents’ families, certainly weren’t at fault that day in 1975, any more than my family was, and yet you and they have suffered as much as, even more than, anyone there. It seems it’s always the innocent who pay the highest price for injustice. It’s seemed that way all my life.

To the still grieving Coler and Williams’ families, I send my prayers if you will have them. I hope you will. They are the prayers of an entire people, not just my own. We have many dead of our own to pray for, and we join our prayers of sorrow to yours. Let our common grief be our bond. I state to you absolutely that, if I could possibly have prevented what happened that day, your menfolk would not have died. I would have died myself before knowingly permitting what happened to happen. And I certainly never pulled the trigger that did it. May the Creator strike me dead this moment if I lie. I cannot see how my being here, torn from my own grandchildren, can possible mend your loss. I swear to you, I am guilty only of being an Indian. That’s why I’m here.

Being who I am, being who you are — that’s Aboriginal Sin.

ABORIGINAL SIN

We each begin in innocence.

We all become guilty.

In this life you find yourself guilty of being who you are.

Being yourself, that’s Aboriginal Sin,

the worst sin of all.

That’s a sin you’ll never be forgiven for.

We Indians are all guilty,

guilty of being ourselves.

We’re taught that guilt from the day we’re born.

We learn it well.

To each of my brothers and each of my sisters, I say,

be proud of that guilt.

You are guilty only of being innocent,

of being yourselves,

of being Indian,

of being human.

Your guilt makes you holy.

NO DOUBT, MY NAME will soon be among the list of our Indian dead. At least I’ll have good company — for no finer, kinder, braver, wiser, worthier men and women have ever walked this Earth than those who have already died for being Indian.

Our dead keep coming at us, a long, long line of dead, ever-growing, never-ending. To list all their names would be impossible, for the great majority died unknown, unacknowledged. Yes, the roll call of our Indian dead needs to be cried out, to be shouted from every hilltop in order to shatter the terrible silence that tries to erase the fact that we ever existed.

I would like to see a redstone wall like the blackstone wall of the Vietnam War Memorial. Yes, right there on the Mall in Washington, D.C. And on that redstone wall-pigmented with the living blood of our people (and I would happily be the first to donate that blood)–would be the names of all the Indians who ever died for being Indian. It would be dozens of times longer than the Vietnam Memorial, which celebrates the deaths of fewer than 60,000 brave lost souls. The number of our brave lost souls reaches into the many millions, and every one of them remains unquiet until this day.

Yes, the voices of Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse, of Buddy Lamont and Frank Clearwater, of Joe Stuntz and Dallas Thundershield, of Wesley Bad Heart Bull and Raymond Yellow Thunder, of Bobby Garcia and Anna Mae Aquash…those and so, so many others. Their stilled voices cry out at us and demand to be heard.

PEOPLE OFTEN ASK ME what my position is, or was, in AIM–the American Indian Movement. That requires an explanation.

AIM is not an organization. AIM, as its name clearly says, is a movement. Within that movement organizations come and go. No one person or special group of people runs AIM. Don’t confuse AIM with any particular individual or individuals who march under its banner, however worthy or unworthy they may be. AIM is the People. AIM will be there when every one of us living today is gone. AIM will raise new leaders in every generation. Crazy Horse belonged to AIM. Sitting Bull belonged to AIM. They belong to us still, and we belong to them. There are no followers in AIM. We are all leaders. We are each an army of one, working for the survival of our people and of the Earth, our Mother. This isn’t rhetoric. This is commitment. This is who we are.

Yes, we can each be an army of one. One good man or one good woman can change the world, can push back the evil, and their work can be a beacon for millions, for billions. Are you that man or woman? If so, may the Great Spirit bless you. If not, why not? We must each of us be that person. That will transform the world overnight. That would be a miracle, yes, but a miracle within our power, our healing power.

MY LEGAL APPEALS for a new trial will continue. We also continue to seek parole or Presidential clemency. In late 1993, and again in 1998, the U.S. Parole Commission rejected my appeal for parole, telling me to apply again in the year 2008. The simple act of changing my “consecutive” life-sentences to “concurrent” life-sentences–a change of one work–would give me my freedom and return to me at least a part of my life, if only my old age. I pray the Parole Commission will make that one-word change.

My appeals attorney, former U.S. Attorney General Ramsey Clark, submitted in November 1993 a formal application for executive clemency from President Clinton, meaning not a pardon but a Presidential order giving me simple release from prison for “time served.” This, apparently, is my best hope for freedom. The request was turned over for review to the Department of Justice, which must make a formal recommendation to the President after reviewing my case.

Nearly five imprisoned years later, I still await that recommendation. I pray hard it will come soon. I pray an eagle will fly off the flagstaff in the President’s Oval Office and at last deliver that long-delayed recommendation from the Attorney General’s desk to the President’s desk. And while the President sits there considering this innocent Indian man’s appeal for clemency, I pray that that eagle will stand there on his desk, stare into his eyes, and join its cry to the cry of the millions of people around the world who have written to the President, appealing for my release. With all my heart I personally appeal to him for his consideration and for his compassion.

I am an Indian man. My only desire is to live like one.

In the Spirit of Crazy Horse

/S/ LEONARD PELTIER